Ilan Gutin in conversation with artist Sarah McKenzie around Tilt West’s 10th anniversary season theme of CHANGE, reflecting on co-founding Tilt West, fostering critical dialogue, and making space for what comes next.

Interview with Sarah McKenzie

Ilan: Hi, Sarah. It’s great to speak with you today, thanks for being here. To start us off, would you mind introducing yourself and sharing a bit about your background?

Sarah: Sure. Thank you, Ilan. I’m Sarah McKenzie and I’m a painter. I’ve lived in Colorado since 2006 and I live in Boulder. I show with David B. Smith Gallery in Denver. I make paintings about architecture and the built environment. I’m also one of the co-founders of Tilt West. Along with Sarah Wambold and Whitney Carter, the three of us conceived of Tilt West back in 2015, then assembled a board and formally started the organization in the fall of 2016.

Ilan: Speaking of Tilt West, the organization is in its 10th season with the theme of “Change”. When you look back ten years ago, when you and Sarah and Whitney founded Tilt West, what kind of change were you hoping to spark in Denver’s creative arts community?

Sarah: At that time, both Whitney and Sarah had recently relocated to Denver. Whitney had been running a gallery in Los Angeles and moved to Denver to be closer to family, and she was working with David B. Smith at his gallery. Sarah Wambold had moved from Chicago, where she’d been working with the Art Institute of Chicago.

In our early conversations, we were thinking about how Denver hadn’t yet achieved the same ambition as art scenes in cities like Chicago and Los Angeles. There were, and still are, many really interesting artists working in this region, and galleries doing strong programming, but the overall level of discourse around the arts in Denver at that time felt a bit parochial or regional. Not as critical, in the best sense of that word.

We wanted to see a more sophisticated level of conversation around arts and culture. The initial impetus was asking ourselves: What could we create that would help drive the conversation in Denver to feel more national or international in scope, and help turn up the volume on the great work that was already happening here?

![Sarah McKenzie (3rd from the left) with fellow curators and artists at Redline [2025]](http://tiltwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/with_fellow_curators_and-artists_at_Redline_2025-1024x695.jpg)

Sarah: Our first idea was actually to create a publication. At the time, DARIA [Denver Art Review, Inquiry, and Analysis] didn’t yet exist. There were art reviews in Westword and the Denver Post, but those were written for a general audience. We didn’t feel there was much arts writing in Denver that was specifically targeted to the arts community or to people with a more nuanced understanding of contemporary art.

We imagined creating something that might fill that gap, but none of us felt equipped to immediately start a publication. That wasn’t part of our professional backgrounds. I had a former colleague who had started an organization in New York called Critical Practices, Inc., which hosted roundtable conversations, very much in the style of how we now run events at Tilt West.

We thought that could be a good starting point. Maybe we’d pursue a publication later, but for now we could host events, get our name out there, and have rich conversations about the arts and see what developed. Critical Practices, Inc. agreed to let us adapt their model, and fall of 2016 became our first roundtable season.

As for becoming a nonprofit, we always assumed there wouldn’t be a way to charge admission or operate as a for-profit organization, but we knew we’d need funding. Becoming a nonprofit just felt like a no-brainer from the start.

Ilan:

I had no idea the Tilt West roundtables were modeled after another organization.

Sarah: Yes, our “rules of the game” document is adapted from Critical Practices, Inc. They were the ones who chose that language for the guidelines. I think they even used the French term les règles du jeu, being in New York, they were very highbrow.

![Sarah McKenzie moderating artist panel at East Window Gallery with incarcerated artists [2025]](http://tiltwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/moderating_artist_panel_at_East_Window_Gallery_2025-1024x796.jpg)

Sarah: Yes. It was pretty wild. I think we were all confident that Hillary Clinton was about to become the first woman president, so it didn’t feel risky to schedule an event for that evening. Then we were all in shock, but we decided to go ahead with it because it felt like a night when people really wanted to come together and process what might be happening in our country.

We had the scheduled conversation, but there was also acknowledgment of the historical moment we were in.

Ilan: That must have been an intense night.

Sarah: Cortney Lane Stell was the first prompter for that roundtable. And even though it was nearly ten years ago, I remember her doing a wonderful job of holding space for people to process what they were feeling, while still helping keep the conversation on track.

Ilan: In those early days, did you have a sense of what Tilt West might become, or has its evolution surprised you?

Sarah: In some ways, it became exactly what we envisioned. We knew early on that we wanted to pursue a publication, and we did eventually produce a journal for three about years before shifting directions.

But we never got overly hung up on long-range planning. We had loosely defined goals, but everyone was volunteering their time, and none of us really knew exactly what we were doing. We figured things out as we went along. There was a strong commitment from the board from the beginning, paired with a sense of realism, none of us were being paid, and we didn’t know yet if the Denver art world or funders would support what we were doing.

That flexibility was a good thing. We never held ourselves to rigid five- or ten-year plans. We were fairly easy on ourselves about meeting goals.

Ilan: After ten years, why does now feel like the right time for you to step away?

Sarah: I’m the only one of the three original founders still involved. Whitney Carter and Sarah Wambold stepped away a few years ago to pursue career changes. Kate Nicholson and I are the only original board members remaining.

There were years when I was doing a lot of the organization’s day-to-day work, and I think there’s a recognition that if an organization is going to last, it has to be bigger than one person. Sometimes founders play an outsized role early on, and that can eventually prevent an organization from growing or changing in the ways it needs to.

At this point, there’s an incredible board in place. It feels like the right moment to step back, trust others to carry the torch, and help ensure Tilt West’s long-term sustainability.

I’ve also become deeply involved in other work, including teaching art inside prisons. That’s where I feel most needed right now, and I know Tilt West no longer needs me in the same way.

![Sarah McKenzie teaching at Sterling Correctional Facility [2025]](http://tiltwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/teaching_at_SterlingCF_2025-1024x683.jpg)

Sarah: In my studio practice, I tend to work in five to seven year cycles. Eventually, I reach a point where I’ve solved the problems the work raised for me. I could keep going, but I’m no longer learning anything new. That’s usually the moment when it’s important to shift gears and try something uncomfortable.

I see a parallel with professional responsibilities like serving on a board. Tilt West has the potential to become something new in its next decade, and that’s more likely if those of us who were leading in the first ten years make space for new people. Tilt West belongs to the arts community; it's bigger than any one person. That’s what gives it the best chance to last.

Ilan: So you see it as something fluid, with a life of its own.

Sarah: Yes. I hadn’t thought about it that way until recently. There were times when I probably resisted changes that felt too far from the original mission. But now I think that’s okay. If the board moves in a new direction, that’s exciting! That’s the evolution of the work.

Ilan: You’ve mentioned your current work with artists in the prison system. Can you talk about how you became involved and why it resonates with you?

Sarah: I originally became involved because I wanted to make paintings about the architecture of prisons. It started as an intellectual curiosity. When I started researching prisons, many people I interviewed emphasized that if I wanted to make work about carceral spaces, I needed to understand the people impacted by them.

During COVID, I reached out to the University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative (DUPAI) to volunteer. I didn’t expect to teach, but that opportunity came quickly. I wound up teaching drawing in the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC) through DUPAI for two years. DUPAI stopped working inside the CDOC in 2023. I was desperate to get back inside to continue teaching, so in 2024 I co-founded the nonprofit Impact Arts with Lilly Stannard.

After decades in the art world, it can be easy to feel cynical about how art functions as a luxury commodity. Teaching inside prisons reminds me of the deeper value of creative practice, how it can restore agency, build community, and give people a reason to get up every morning. That work has re-centered me in why I make art at all.

Ilan: I think that really speaks to the power of art, how it can have such a profound effect on people who are incarcerated.

Sarah: Yes, definitely.

Ilan: And like you said, it gives them a reason to get up, to feel motivated, and to accomplish something they have control over in a world where they don’t have much control.

Sarah: Yeah, right. It also really builds community. I teach at Sterling Correctional Facility, and there are men who are sort of “art friends” who probably wouldn’t talk to each other if not for the fact that they’re both artists. Our prisons are very racially segregated, so it’s meaningful to see how art can transcend that and become a kind of glue that allows people to connect across differences.

Ilan: Is it complicated for you to move between those spaces, working with incarcerated artists and then returning to the commercial art world, like attending an opening at David B. Smith or another gallery? What does that feel like?

Sarah: I wouldn’t say it’s really hard. Through my curatorial work over the past few years, I’ve been trying to bridge those two worlds, creating opportunities for artists in the prison system to have their work seen in contemporary art spaces, and maybe to challenge the contemporary art world a bit.

I’m not the only person doing this. Curators around the country have led the way, and if anything, I’m late to the conversation. I don’t give myself much credit for the idea itself. But I do think there’s a growing recognition that the contemporary art world should be open to the stories and perspectives that artists in the system can share. It’s not enough to say, “That’s outsider art, that’s something over there.” I’m trying, at least in our region, to suggest that this work is actually related to the same questions many of us are already thinking about.

I will say that I’ve become impatient with exhibitions that are only about good-looking objects. I don’t want to dismiss beauty or suggest the work lacks depth, but because of this prison work, I’ve come to value art that asks me to think about something beyond, “Wow, that’s beautiful.” When I go to galleries or museums now, I find myself placing more value on work that challenges us to think about society in deeper ways.

Ilan: I think that comes through in your own work. Your paintings are beautiful, but they don’t glamorize the prisons you depict. They feel very frank and stark, and they’ve made me think about things like the lack of windows and what it might feel like to exist in those spaces.

Sarah: Thank you! That’s my hope.

Ilan: What parallels do you see between the conversations Tilt West has fostered and the conversations you’re facilitating through prison arts programming?

Sarah: Going back to the fact that our first roundtable happened the day after the 2016 election, I think there’s a lot we didn’t anticipate when we were imagining Tilt West in 2015 and early 2016. We expected a certain level of intellectual conversation around arts and culture, but we didn’t anticipate how central politics, activism, race, cultural identity, access, and representation would become to our programming. We’ve gone through so much political and social upheaval over the past ten years, and all of that has filtered into Tilt West’s roundtables. We’ve tried to reflect what our community has grappling with. Whether it was roundtables on AI or NFTs, we paid attention to what was rising to the surface in the broader arts discourse and made sure our conversations addressed those topics.

Tilt West has become much more socially and politically engaged than we initially imagined, and I think I have as well. That engagement led directly to my interest in prisons and to reorganizing my creative career around working with incarcerated artists. It’s all interconnected; Tilt West’s evolution paralleled my own, and that changed me as an artist.

Ilan: I’d love to talk a bit about your own art practice. How would you describe the themes and core questions you’re pursuing right now?

Sarah: That’s an interesting question because I’m very much in a transitional year. As I mentioned before, most of my projects have a five- to seven-year arc. Before the prison work, I was making paintings about exhibition spaces and museums, thinking about institutional architecture and how it communicates social codes and cultural values.

That led me to prisons, which are also institutional spaces designed to communicate authority and state power. This past spring, I had a solo exhibition at David B. Smith Gallery that showed several of my prison paintings alongside new museum paintings, exploring the parallels between those spaces. Museums and prisons may seem very different, but they’re more similar and connected than we might imagine.

Now I’m thinking about what comes next. Over the summer, I participated in a group exhibition in Bucharest, Romania, my first time in an Eastern European city that was part of the former Soviet bloc. Seeing architecture from the Ceaușescu regime made me think about how buildings communicate state power or the authority of individuals in power. Pair that with what’s happening now, like Trump tearing down part of the White House to build a ballroom, and I’m still very interested in institutional space and power, but possibly beyond prisons and museums.

I have a residency in January where I’m planning to experiment, maybe even return to drawing. Ask me again in a year, and I’ll have a better elevator pitch for the new work.

Ilan: Looking back at Tilt West and the community you helped build, what feels most meaningful to you?

Sarah: One thing is the simple power of bringing people together in a room. Over the past decade, more and more of our interactions have moved online: Zoom meetings, social media, text. We spend less time talking face-to-face, even in our personal lives.

There’s something powerful about bringing thirty people, often strangers, into a room for ninety minutes, without screens, to focus on a shared conversation. That’s really our secret sauce. We didn’t invent it, Critical Practices, Inc. did, but it’s rare in Denver, and that’s why people keep coming back.

I was reminded of this when my new nonprofit, Impact Arts, hosted a roundtable for people volunteering inside prisons. None of the participants, except me, had ever attended a Tilt West roundtable. By the end, everyone said, “We need to do this more.” It reinforced how essential these conversations are, regardless of topic.

Ilan: Even when the topic isn’t something I know much about, I still find the roundtables valuable.

Sarah: Exactly. For people in academia, that experience of sitting in a room and discussing a shared topic is familiar. But once you leave school, it disappears from daily life. The roundtables bring that back. You don’t need to be enrolled in a class to experience the value of collective thinking.

Ilan: Do you hope the same thing happens with Tilt West’s publications?

Sarah: In some ways, yes, but it’s different. We originally wanted to elevate discourse through publishing. Now that publications like DARIA exist and do that work beautifully, we’ve had to rethink our role.

Our print journals were modeled after the roundtable structure: a shared theme with many contributors responding through different formats, poetry, essays, visual art, even music. The issue was that the labor involved in producing each volume far outweighed the readership we reached.

Now the website functions as our publishing platform, and the relationship between curated content and our roundtable events is still being figured out. That’s something I leave to the current board. We’re in a transition period, still shaping what this next phase looks like.

Ilan: What do you hope Tilt West continues to be over the next ten years?

Sarah: I hope the roundtables always remain at the heart of the organization. They’re what Tilt West is known for, and I don’t think any other group in Denver is offering something quite like them.

I also hope Tilt West continues to bridge different creative communities– visual arts, theater, dance, spoken word– that don’t always feel connected. At its best, Tilt West acts as a kind of glue, creating space for dialogue across disciplines.

Ilan: Is there anything else you’d like to add before we wrap up?

Sarah: I’m curious to see how Tilt West navigates technology in the future. We’ve historically kept events very low-tech, resisting streaming or heavy digital mediation. As younger board members step in, new perspectives will shape the next decade. I’m excited to step back and watch where it goes.

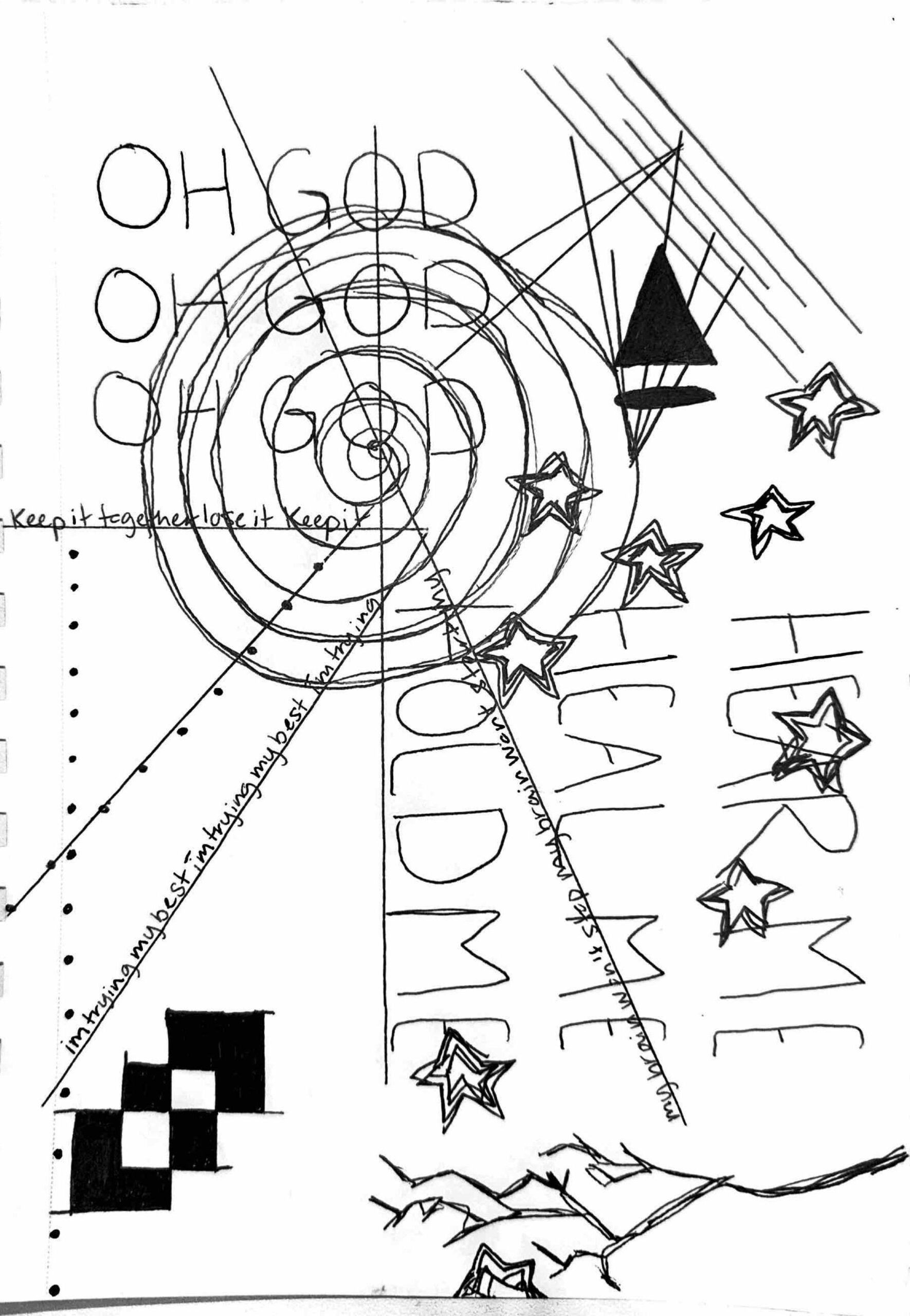

The Vitruvian Man stands with his arms outstretched, measured by geometry

and God. Leonardo's lines follow Vitruvius's law: that every body, like

every temple, must be strong, functional, beautiful.

My arms flap

not in golden ratios

But in flailing attempts failing attempts

As I try to dance

Or exist

As a perfect man woman artist

A studio drawing, uncovered in a notebook. Musings of the human body that

have spread across centuries and continents. A representation of the

Renaissance: art, science, and divinity questioned at once.

I attempt to postulate

Art as god To relate

Artist to nature

To say:

We are nature.

Queer body,

Trans bones,

Sacred being.

The Encyclopedia Britannica notes that da Vinci conceived the drawing of the

Vitruvian man "as a cosmografia del minor mondo (cosmography of the

microcosm). He believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy for

the workings of the universe."

A divine construction.

I don't measure to the perfect

proportions

of the Vitruvian man

or the dexterity of da Vinci's hands.

But I do believe

that the human body

is a microcosm

for the workings of the universe.

A divine construction which allows me to breathe.

To dance.

My cells

that grow

and change

and multiply

and create

Imperfect

but alive.

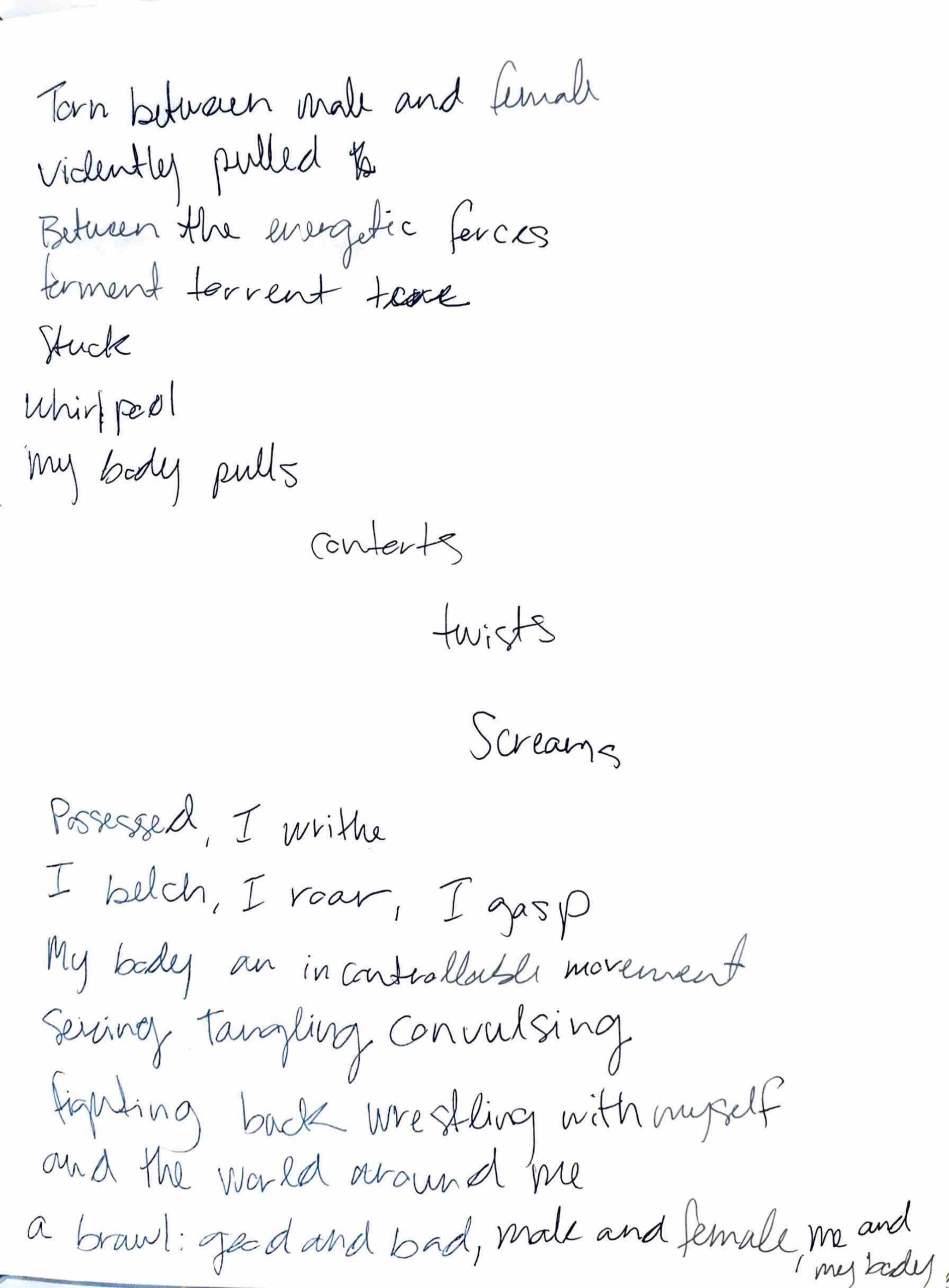

![handwritten text on paper saying "it took me 23 years to remember I have a body, to learn I have a body, to declare I have a body. My hips my heels my hair, my bones exalt in the force of life, I stretch so high I eat the clouds, and for a moment, [I feel god] crossed out, I'm an angel"](http://tiltwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/IMG_8038-scaled.jpg)

Here at Tilt West, we’re thrilled to be launching our 10th season of roundtables, all relating to this season’s curatorial theme: CHANGE. As we begin our 10th year, it’s rather amazing to look back on all the changes our nonprofit has experienced since we held our very first event on Wednesday, November 9th, 2016 — one day after a Presidential election which certainly changed the course of the country. It has always been part of our mission to respond to current events and provide a platform where members of the Colorado creative community can come together for a free and egalitarian exchange of ideas. We’d like to think we’ve held fast to that commitment, whether exploring the role of the arts in activism; discussing the lure of spectacle in contemporary society; weighing the perils and opportunities of technological advances; or delving into the necessity for play as a critical component in imaginative world-building.

We’ve changed in so many ways: bringing our itinerant roundtable events to arts and cultures venues throughout the Denver metro area and beyond; introducing an annual print publication, then pivoting to focus on our website as our publishing hub; adapting to Covid lockdown and offering virtual roundtables over Zoom; then returning to the in-person event model which has always been central to our organization’s identity. Our volunteer board has changed over the years too and we have been fortunate to have many talented people contribute to the success of Tilt West. As we begin this season, only two of our original board members (myself and Kate Nicholson) remain, and they will both step down in December, passing the torch to the incredible team who will carry Tilt West into its next chapter.

Join us for this season of CHANGE and continue to tilt the conversation! The theme invites us to reflect on what has shifted over the past decade - in our lives, the world, and our art communities - and what we hope to see in the next ten years. We are excited to host a season of roundtables and programs exploring transformation in all its forms: adaptation, reinvention, resilience, and the creative and societal shifts that shape our cultural landscape.

Check out our lineup of roundtable topics for the 2025-26 season. We hope to see you there!

- CHANGE: Culture Under Pressure

- CHANGE: Nostalgia, Fluidity, and Stagnation

- CHANGE: Disability, Illness, Change, and Time

- CHANGE: Deconstructing American Values

- CHANGE: The Body as Battleground

The almond tree in Amaki’s compound house was dotted with tiny yellow oval-shaped fruits that willed their way to the ground at the slightest urge of a passing breeze. At dusk, the sky above would fill with hundreds of straw-colored fruit bats making their way across the city, seemingly guided by the warble of the call to prayer from a distant mosque. Growing up, this compound was the fertile ground for my imagination. It was modestly sized but pliable, folding itself into the universes of a child’s mind and the heart of a family’s world. This piece is a sonic exploration of personal history, and an homage to the matriarchal figures of my life who, through love and sacrifice, built structures of safety that made unbridled play possible for generations after them. I embrace an intuitive process of improvisation, turning an experiment with analog hardware and virtual instruments into a practice of performance as listening, straining to once again hear Amaki’s voice.

In response to our season’s theme, PLAY, and our roundtable conversation PLAY: Collaboration and Co-Creation, Tilt West invited Steven Dunn and Katie Jean Shinkle to publish an excerpt from their co-created novel, Tannery Bay.

“This collaboration between Steven Dunn and Katie Jean Shinkle was born out of a deep friendship and mutual love for each other’s previous novels. We were also exhausted by ill representations of black and/or queer people in popular media, so we wanted to write together about our own people in a way that allowed them to be their full selves while experiencing joy, grief, friendship, and community.”

July 4

Once upon a time across the bridge from the dilapidated casino, Auntie Anita is boiling water, adding flour, stirring and stirring until smooth. She’s making wheat paste. She tells Uncle Gerald to get the paint rollers and brushes from the cabinet.

“What time you meeting Cristal today?” Auntie Anita asks.

“Somewhere around one or two,” he says.

“I’ll be back around noon to take the baby out to play,” she says.

Auntie Anita pulls coffee cans of wheat paste from under the cabinet, slaps the bottoms of the cans into her palm, and places them in a dirty green canvas bag. She slings the strap over her shoulder and kisses Uncle Gerald and Cora Mae on their cheeks.

“Maybe I’ll bump into y’all’s weird-ass friend while I’m out there,” she says to Otis and Joy, who are untangling fishing nets for her.

“Anyway, shouldn’t it be your friend since you the one who been dreaming about her?” Joy says. Auntie Anita laughs and walks out, leaving the fishing nets.

Auntie Anita’s newest art form is wheat pasting, and she was in the habit of pasting at night across the bridge, but the cops started watching too closely, sending more officers than usual on foot and bikes, which means anybody can do anything at night in Tannery Bay because all the cops are busy looking for whoever is papering up the town. Now Auntie Anita papers during the morning, the ass- crack of the day she calls it, right after all the cops change shifts. She knows it’s not dangerous because no one expects an old woman to be the one papering FUCK YOU AND JULY using her own hand-drawn letters framed by roses she stenciled herself on the police station and the tannery. When she makes art in her neighborhood, she only papers or paints or sculpts scenes of togetherness: dancing, hugging, sitting on porches, playing cards, eating around large tables. Or the giant rainbow trout nobody has ever seen. Or huge portraits of folks in need of peaceful memoriam, remembrances she calls them.

Willie Earl says the portraits of folks are judging you because you fucked up, or watching over you because you fucked up. Once a week Willie Earl walks the kids and the teens through the neighborhood, and always stands scratching his gray beard and pointing upward to the mural saying, “Check this out, youngbloods. Look into this person’s eyes and feel deep within yourselves when you notice the subjectivity change, when you can’t tell if you looking at the portrait or the portrait is looking at you.” He laughs his giant laugh and walks away, but his laugh stays with the kids with its arms around their shoulders.

Willie Earl then walks up the street to the side of Harold & Hattie’s Haberdashery and stands in front of the large mural of his wife, Mildred. He looks at her smooth, brown, peaceful face and soft eyes until she looks back at him, and Willie Earl feels like a mural—large and colorful and soft and highlighted in all the best places—and it’s here in this plane, this plane of porousness between worlds where Willie Earl knows Mildred isn’t dead. He cries gloopy paint tears until his laugh leaves the kids and returns to cradle him like a baby.

Today when Willie Earl melts inside of Mildred’s mural, he feels something off. There’s a damn disturbance, he thinks as he’s floating inwards, toward the center of the mural, and he’s looking around to find this damn disturbance and sees his overalls change into a dark-blue suit with gray pinstripes and a pink paisley tie. Nice threads, he thinks, still floating until he lands on the yellow patch of paint where he usually meets Mildred for a dance. She isn’t there. But he sees a head pushing up through the yellow paint and he wants to stomp on it because it ain’t Mildred’s head, Mildred don’t have wet stringy hair. It’s the woman in waders standing in front of Willie Earl, motioning to his suit. He says, “I do look nice, thank you, young lady. Now where’s Mildred?” She gives Willie Earl a cockleshell and lowers herself back into the yellow paint. Willie Earl’s laugh reaches in and pulls Willie Earl back onto the street in front of the mural. He has on his regular old overalls again.

Other places across the bridge, Auntie Anita sculpts symmetrical symbols made up of triangles and circles connected by lines with some X’s here and there. Auntie Anita says she doesn't know what they mean, but she feels like she needs to mold them because they are in her somewhere, like her song. She leaves little statues of symbols on gravestones, in the alley behind the casino, on manhole covers in the middle of the streets, on the concrete pillars beneath the bridge, at street intersections.

Auntie Anita walks back in the house at noon like she never left, canvas bag empty. She tells Otis to bring more flour home from the dumpster in the casino alley when he goes back to work. She tells the same to Joy. She plops down in a chair and Cora Mae climbs into her lap. Uncle Gerald stands over the stove, tasting the broth from his oxtails, fixing everyone a steaming bowl before he leaves to meet Cristal. He hugs Otis and Joy like they are stuffed animals, then he kisses Cora Mae and Auntie Anita on their foreheads. After kissing Auntie Anita he wipes his lips with his forearm and says, “Sweaty-ass forehead, you musta been working hard.”

Cristal sits by the bay’s edge across from the casino and throws rocks into the most purple parts where the water looks like oil in a rainbow surface skimming the top. When she was young, she and her friends would swear there was a monster in the bay, a dinosaur history left behind. The chemicals on the water hold the rocks a second longer than normal, like gel, plunging them to the bottom slowly. There is a rumor a coworker at the casino tried to have sex with the water once because he said it felt so good, held him so tightly, but the coworker adamantly denies the rumor, and Cristal feels he would tell her the truth of whether he tried to get down with the gel-water chemical bay or not. She laughs as she throws the next rock, watches it sink slow. Vaginas don’t feel like gel-water chemical bay shit, she thinks, and it’s clear he ain’t never even been inside one. She wipes her hands on her jeans; her red nails are chipped, due for a new manicure. She knows she’s going to rip the rest of the color off with her teeth anyway so there is no use in keeping up with it. The air only feels cool to her down by the water. The water alleviates the heat, even though to even be near it feels dangerous. The same coworker who ain’t never been in a vagina swears the scars on his arms comes from being in the water, the chemicals eating his flesh. Cristal thinks, so I don’t know. Bad fucking water.

She wraps her body around itself, pressing the bones of her chest into her knees, letting her light red, curly head rest, closing her eyes for a minute. She can hear the barge downriver, the chug chug chug of the motor. She unclenches her jaw, relaxes her eyebrows, it feels good, she thinks, to let the body go. She thinks about Lexus, her round belly, and her thin shoulders, and her long neon green hair that she never does anything with. She thinks about her crooked smile, her chipped front tooth, such a curved dent looking almost natural in her mouth. Her heart-shaped lips, a movie star. Her blue Dickies work pants, her blue Dickies work shirt with the name Gary in a red oval on the left side. Cristal wants to kiss Lexus every single time she sees her. Lexus has no idea how Cristal feels, and she will soon, she thinks as she kicks the sand in a childish fit. Lexus is so cool, and just like generally never causes a ruckus except in love. She is always in love with somebody new! I love Lexus, though, like I really love her, and I want her to be with me, only me. She pulls out the small notepad she scribbles all her thoughts in and writes on her To Do list between Buy Milk for Auntie and Return Book to Joy as number eight: Get a Grip on Yourself, Girl.

The bay starts bubbling at Cristal’s feet. When she looks at the horizon, there is the woman in waders walking on water. Cristal closes her eyes. She tries to breathe deeply, but her breaths keep catching in her throat. She opens her eyes and the woman is still there, coming faster toward her. When am I going to tell Lexus I love her, she thinks. She gets up and tries to breathe deeply again like Lexus taught her, letting the air fill her down her back and up her neck and holding it for two counts before slowly letting it out until the next breath is organic and a type of buoy. I gotta get to Uncle Gerald, she thinks. She runs away right as the woman in the waders reaches the shore, sprays her legs with bay water, and disappears.

Uncle Gerald is already sitting on the concrete seats in the first row of the old amphitheater with a small pot of oxtails, two bowls, and two spoons. Cristal walks in scratching at her legs, smiling a little. She sits and Uncle Gerald says, “You smiling because you and Lexus finally going together? You asked her? How’d you do it? Like how you practiced on stage yesterday?”

“No,” she says, “We’re not going together yet, and I didn’t ask her.”

“Ah, fine fine, you’ll do it when you ready,” Uncle Gerald says, spooning some oxtails into Cristal’s bowl. “Why you smiling?”

Cristal slurps some broth straight from the bowl and nods her head to let Uncle Gerald

know the soup is good as usual. “I don’t know, things are starting to feel funny. Over at the bay in front of the casino right before I walked over here this woman was walking on the water coming at me. She sprayed my legs.” Cristal shows Uncle Gerald the red splotches on her ankles and shins. “Do you believe me? I swear it happened.”

“Well goddamn! We been seeing her too!” Uncle Gerald flails his arms but accidentally knocks the pot of oxtails over. The pot clangs on the ground and the broth splashes like liquid usually does, but it starts to wobble and collect itself into the shape of a cockleshell.

“Let’s get out of here,” Cristal says.

Uncle Gerald rubs his shoe into the cockleshell-shaped broth. It splashes out of shape again but pulls itself back into the shape of a mason jar, changing to the distinct golden color of Uncle Gerald’s hooch. His throat tightens and eyes widen.

“You said that right, Crystal!” Uncle Gerald says. He bends to pick up his pot, but shakes his head no. “You can stay here,” he says to the pot, “I ain’t bringing this bad juju back in the house.”

They leave the amphitheater. Back on the bridge, silent even though they’re never silent when walking home. Cristal says finally, “Who is the lady, anyhow?”

“Hell, I don’t know,” Uncle Gerald says, “maybe she’s Saint Whatever-the-Fuck-You-Need to whoever sees her. I need a new pot to cook my oxtails in.” He cups his hand around his mouth and yells over the bridge into the bay, “I need a new pot, saint lady!”

“I think the woman got something to do with Anita, somehow, some kinda way.”

Cristal leans over the rail to spit into the purple bay, and notices four of Auntie Anita’s small statues of people standing in a row at the base of one of the concrete pillars. The statues are in various poses—hands on hips, hand covering eyes shielding from the sun, arms spread for a hug to no one, fishing but leaned back like a big fish is on the nonexistent line. Cristal hears a deep bloop in the bay a little ways out and lifts her head to see, but nothing. When she looks back at the statues, they are huddled in a circle with their arms on one other’s shoulders, and the tops of their heads touching. She blinks hard and shakes her head, and the statues are back to standing in a row in their original poses.

“Uncle Gerald, wait!” Cristal jogs to catch up: “Speaking of Auntie, did you hear about the casino owner is taking credit for Auntie’s art again? Now he’s built a room sticking halfway into the alley. He’s charging those rich folks up in the Hills an arm and a leg to see it, some kind of ‘VIP exclusive’ ticket scheme. I know you said you needed to figure out a way for Auntie to get some of the money.”

“I saw that mess in the newspaper. You know they been doing it for forever, taking everything everybody else do, like they did with my juke joint.”

“What are you gonna do?” Cristal says, stopping to pull Uncle Gerald’s arm.

“What do you mean me, goddammit. This is a we situation.”

“Well, what are we gonna do?”

“This what Imma do, Imma go to that casino, bust up in that muthafucka, steal all the coin from all them slots, then flip over all them blackjack tables, then go the office, steal the safe, strap that muthafucka to my back and crawl my big ass out—”

“But, Uncle Gerald—”

“Hold on, I’m on a roll . . . then Imma drag that safe across this goddamn bridge to the house and dump all the money in Anita’s lap, cuz you know she gives and gives to everybody so we gonna give her something back.”

“I don’t know about all of this.”

“And then, Cristal, you and your lil girlfriend are gonna blow up the casino, the newspaper office, and the goddamn tannery.”

“It’s getting kinda late tonight, Uncle Gerald, but okay, I’ll blow up whatever tomorrow.”

“No matter what, we should be the ones taking people to Anita’s art, right? I mean, who else knows it better than we do? I don’t know, let’s talk to Joy and hatch a plan. We just gotta keep this from Anita cuz we gonna surprise her with a lot of money.”

He rubs his hands together and puts his arm around Cristal’s shoulders, and she puts her arm around his waist. They walk a little further down the bridge into the graveyard.

Tannery Bay is available for purchase from the University of Alabama Press.