"Immersive" is a big buzzword these days. For the last decade and some change, immersive experiences have offered a counterbalance to the flatness of our digital lives, in which we stare into a two-dimensional portal for hours on end. (Is there anything more indicative of the modern condition than one’s weekly "Screen Time Report"?) In this two-dimensional world, one can zoom into a photo of a distant geographic point via Google maps, but can’t smell it, or feel its temperature on the skin, or hear the way the wind sounds whistling through a far-off tree. This access-to-everything, sensual-experience-of-nothing life has everyone from technologists to game designers to marketing agencies clamoring to deem their particular product "immersive." The "immersive" label promises to lure a target audience by offering something more volumetric than what they can glean from their ubiquitous six-inch screens.

But what distinguishes the marketing concept from an artform? I’m not one to get too hung up on policing what constitutes immersive art, but it’s probably also a cop out to apply Jesse Helms’ definition of pornography: "I know it when I see it." I admire folks whose definition of the term "immersive" is not an attempt to claim or gate-keep it, but to assist those who desire to get after it, create it, and understand it.

At April’s Tilt West roundtable, PLAY: Imagination and Worldbuilding, prompter Courtney Osaki-Durgin, a gifted immersive maker, introduced the writings of Margaret Kerrison who authored three books on immersive work.[1] The goal of these books is to establish guideposts for creating immersive experiences, informed by her work as a former Disney Imagineer and on several prominent immersive experiences, such as Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, Avengers Campus and the NASA Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. Kerrison identifies five core tenets of successful immersive works. They:

-

- Are emotional

- Engage all senses

- Create a believable sense of time and place

- Invite us to participate and play

- Promote social interaction

Courtney used Kerrison’s writings as a launchpad (pun intended) for a discussion about the fourth aspect–how we play in the immersive container. As a creator of immersive theatre, I was thrilled to be in the mix for this conversation.

A few concepts kept surfacing in the discussion. The most significant was that in order to play in an immersive experience, folks need a feeling of safety. But that safety, I think, wasn’t defined simply as physical safety . The phrase "in good hands" popped up more than once.

There is much talk of safety in the theatre industry these days, and I find myself a little conflicted about it. Of course I want folks to be physically safe–to believe otherwise is psychopathic. But I am a proud Gen Xer who grew up in Houston, riding my bike until sundown without my mother knowing where I was, catching frogs in the bayou water that contained god knows what, climbing magnolia trees and hanging out with neighborhood pals on precarious branches for hours at a time. These early doses of freedom and adventure, of being a part of the wilder, sensual world, are something I aim to capture in my own work, especially in the outdoor immersive pieces that my company, The Catamounts, creates. So that phrase "in good hands" feels crucial. How can immersive creators invite audiences into their spaces, and encourage them to make themselves vulnerable to play and participation and the unknown? We have to make them feel they are "in good hands," to create a container, but one not too restrictive that allows for growth and adventure to unfold.

A tangent with a point: I used to be terrified of flying until I directed a play about a plane crash. The piece, United Flight 232, was based on a detailed account of a tragedy. My research, a necessary part of directing such a play, revealed that pilots are incredibly well trained, and their responses reflect this training even in moments of rare catastrophe. Each time you board a plane, you are in extremely good hands. As someone who loves travel and adventure, I flew in spite of my terror. But now I fly reassured that each time I travel, there is someone at the helm who is as knowledgeable about that mode of transport as it gets. This allows me to relax and go on the ride, to feel thrilled at the prospect of a new destination and new experiences.

How can immersive creators assure their audiences that they are in good hands so that the audience can relax and go on the ride? We identified few key things during our robust conversation:

- Hospitality: ensuring that audience members are greeted with warmth and welcome.

- The offering of food and drink, a gesture of hospitality.

- Ritual, structure, or a form to connect with, that is already known or quickly knowable.

Any good host knows you greet your guests with warmth, an offering of food and drink, and an idea of what to anticipate for the evening ("We’ll sit down to dinner at 7.") This allows a guest to relax, to be open to the spontaneity of the evening, and even to the surprise.

I want my audiences to feel safe physically, yes, and I want them to feel safe to play. I know that the latter will draw them into the same world my performers inhabit. As someone who has worked in theatre for over 30 years, I can tell you that there is nothing quite like being in a play, when a director sets up a room of experimentation, rigor, wonder, and joy. Some of my richest relationships have grown out of the rehearsal and performance process, as brief as they can be. A good rehearsal space is like those hours spent with childhood friends in the branches of a magnolia tree: ostensibly precarious but exhilarating and free. And what an aspiration, to create that same space for performers and audiences alike.

To experiment, to participate, to engage, to be in relationship with the narrative, you have to feel you are "in good hands." And so that is the task, for we immersive creators, both to be those good hands, and identify ourselves as such.

Notes on Failure (aka Notes on Performance and Activism)[1]

It’s the difference between giving up and not giving up.

– Johanna Hedva, How to Tell When We Will Die, 2024

For Caliban could only fight his master by cursing him in the language he had learned from him, thus being dependent in his rebellion on his “master’s tools.”

– Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 2014

Dear reader,

It’s May.

This essay is a playful—albeit challenging—experiment. It is a process of complex embodied thoughts. It is a reflection on the intersections of performance, activism, and personal experience, and how failure operates within these spaces—not as an endpoint, but as a site of continuous transformation. It raises more questions than provides answers. And much like unifying the body and mind into one entity that operates interdependently, it merges the failure-success binary into a constant state of becoming within space-time.

There are too many complex themes tied together here, so I offer just a momentary peek into the entanglement of performance, activism, failure, and how they intersect within my life.

In January, I started writing unsent love letters to people, places, things, and concepts. The idea was prompted by a virtual writing course I was taking called Fuck Writing taught by Johanna (yo-haw-nuh) Hedva (head-vuh). If you know me, you already know how deeply rooted my obsession is with Johanna. A few mornings after the March 10th Tilt West Roundtable, I set my ten-minute timer and wrote them for a second time.

“My dearest Johanna—I dreamt about you last night and it was such a sweet dream. I rarely have sweet dreams; they are usually nightmares. I was visiting you in LA because you were going to help look over some papers I wanted to publish into a book. It was the first time (well, I suppose the second time) we’ve met in person. You picked me up from an unknown and unrecognizable coffeeshop. You were driving one of those vans that’s all decked out with accessibility tools. You had the driver seat pushed closer to the passenger seat so that you could only drive with your left arm (I thought it was so you could be closer to me).”[2]

They were constantly on mind in mid-March because I was taking another one of their online courses called Death Writing while reading their newest publication How to Tell When We Will Die. As I read their chapter titled “The Freak,” I thought of my younger-New Orleans-self and the romantic nature of finding freaks to fuck—fantasies that never came to fruition because I was too scared that sex would cause my immediate and spontaneous death.

For context, I was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis at age five and have since been diagnosed with a slew of other diseases and disorders. I was taught to embody that the only intimacy that was “safe,” “secure,” or allowed could be enacted by medical professionals. But I never felt safe or comfortable when I was poked, prodded, probed, pricked, and squeezed—i.e., penetrated—in the hospital and clinic. So, I learned to disconnect, separate my mind from my body, disembody. I still have issues with intimacy, love, touch, sex, and most importantly, trust. My inner, irrational gummy bear is constantly afraid that everyone is out to get me, especially when someone I just met tells me “You’re so beautiful” or “I love your body.”

But more on this later.

Performance art was formally presented to me by my mentor eight years ago when I was completing my second master’s degree at the University of Denver. It is an artistic practice that raises questions, disturbs the public, and allows for few precise answers. It is intentionally difficult in that the underlying premise is to avoid the comfortability that other art forms, like painting, might induce within a viewership.[3] Like the protests and violent events taking place at home and across the world, performance art, and especially my performance art, is often characterized as painful, perverse, and provocative. It is activism. It is a tool to both “unseat a complacent public and its view of the value of art” and create embodied connections between myself and others.[4] For me, “the art” happens at the moment when I am interacting or engaging with an audience member—i.e., the brief relationship that forms between me and a viewer during a performance and then disappears (but still exists) when the interaction ends.

As a medium that encourages both personal and collective exploration, performance art allows for play, risk, and experimentation in real-time. I find it liberating because it creates space for failure not as a defeat but to generate new understanding. Performance art, therefore, is a realm where experimentation and failure are essential parts of the process.

The unknown—embracing the chaos and unpredictability of failure—becomes a vital site of transformation and growth. This realization, stemming from both my personal life and my artistic practice, challenges the conventional view of failure as something to be avoided. When we push beyond the boundaries of success and failure, embracing the risk of the unknown, we open the possibility of creating something entirely new.

In April, I presented a nine-hour performance at the Emmanuel Gallery on Denver’s Auraria Campus called Visiting hours under the covers. I wanted to experiment with my fear of bodily intimacy by inviting consenting participants to join me under the blood-stained blankets of a hospital bed. Going into the performance, the initial questions I asked myself included, “How have my early experiences of being ‘touched’ by medical professionals impacted the way I experience bodily intimacy today? Can my bodymind learn/relearn/unlearn how to distinguish between ‘clinical contact’ and physical intimacy that can be comfortable and pleasurable?”[5] My hope was to discover new and unfamiliar relationships, narratives, and movements with each one-on-one interaction.

In my performance work, I often create rules or instructions for the audience as guiding structures for participation. This is where failure plays an important role in my work, because participants almost never interact with me or perceive the performance work the way I intended. It’s as if I always set myself up for failure when I do my performances.

What happens when the rules are ignored or broken? How does experimentation thrive when we embrace the unknown, when we allow the process to be chaotic rather than controlled?

The instructions included on the wall near the hospital bed were direct.

To participate, you are required to follow these instructions:

- Enter the installation at the foot of the hospital bed

- Put on gloves and a mask

- Slowly get into the hospital bed [or sit or stand near the bed][6]

- Visit for about five minutes

- Exit at the head of the hospital bed

“It’s interesting to think about consent here. Perverse performance frequently foists power relations upon the audience member that they may or may not have consented to. When one decides to attend a performance, this is generally understood. One accepts that one does not know what will happen exactly.”[7]

After the third day, I left the hospital bed feeling stiff and perplexed, but excited about the prospects of what I had experienced. with more questions than I had answers. Only one participant I didn’t know personally, out of six individuals, actually got under the covers with me. What was it about the performance that made people scared to get in the bed with me? What were the fears they had? Were they scared of me as a “sick” body? Were they scared that I might harm them since I was a stranger? What does it mean to connect with a stranger? Was it the fear of being in proximity to a “dying” body of someone you don’t know?

Even though not everyone got under the covers with me, critical engagements still occurred. From afar, I was an object. Many visitors mistook me for a mannequin or a “dummy.”

Many college student visitors understood the “care partner” role to mean “doctor or nurse.” Instead of following the instructions, they asked me “How are you feeling today?” or “How long have you been here?”—akin to the 7 a.m. nurse who’s starting their first shift of the week.

I often forget that care is an integral part of intimacy and vice versa. Johanna defines care as an action that combines intention and attention.[8] It’s the moment when you ask the hot femme you’re making out with “Is this okay?” or “Are you okay?” Care is about checking in. Care is not purely for an individual or those closest to that individual. Care is about caring for literally every human because we are human. What would this earth feel like if we were “naturally” inclined to love and care for every being rather than naturally inclined to be fearful of them?

The concept of success in patriarchal capitalism is often tied to completion or achievement. In the medical field, success is married to the linear progress from “sick” to “healthy.” But many of us will never be fully healthy. So why not shift the paradigm to one that accommodates experimentation (which medicine invariably entails, especially for disabled bodies) and ongoing engagement without focus on a particular outcome that may neither be attained nor attainable. As Johanna reflects in How to Tell When We Will Die, activism—much like performance—rarely succeeds in the traditional sense. It is in the repeated failures and the perseverance to continue despite them that new meanings are found. “I like thinking that activism will always fail, because it means that the decision to take action, to act as though what we do matters, even in the face of certain defeat, is its own purpose…It’s about what we can do, right here, right now, for each other.”[9]

This work is a reminder that nothing is wasted, or a failure. Experimentation is all data. It is a practice of emergence. Like adrienne maree brown explains, “Emergence emphasizes critical connections over critical mass, building authentic relationships, listening with all the senses of the body and the mind…It is a system that makes use of everything in the iterative process.”[10]

When Sylvia offers the allegory of Caliban’s inability to break free from Prospero in Shakespear’s The Tempest, she is suggesting that we must find unknown pathways that derive from outside the “master’s tools” embedded within us (i.e., patriarchy, capitalism, colonization, all systems of oppression).

So, the next time you see me under the blankets of a hospital bed, you better come get under the covers with me.

I love you.

Love, MG

The memory is this: playing on a beach called Bombinhas (meaning “little bombs,” named after the sounds of the crashing waves) in the southern Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. A child about my same age was nearby with her mom, and we start to play together. I could not understand a word she said, and she could not understand me - her Argentinian Spanish sounded like puffs of sounds to me, as my Brazilian Portuguese probably did to her. But we shared a common language: the language of play. We were fluent in beach toys, sand, and sea. Not understanding each other’s spoken language did not inconvenience our playtime. What lasted in my memory was the fun I had with my friend of one day.

Play is a universal language. Children can discover and invent play anywhere. Play can thrive even amidst hardship. Play can activate the imagination to transform pain into joy.

Two photographs document this transformation:

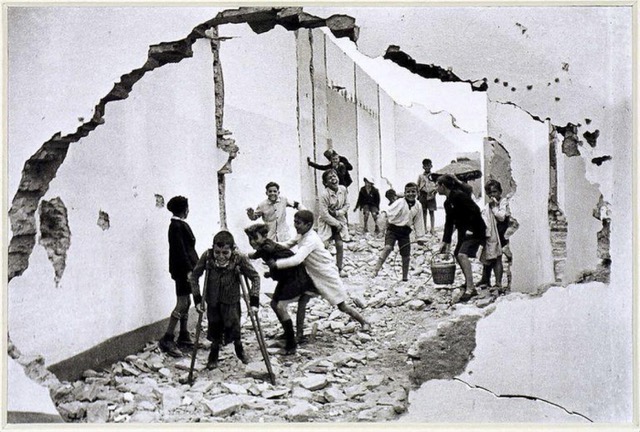

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of a group of children playing in the rubble of destroyed buildings, taken through a hole in the wall. The ruined environment suggests violence, and the nearest child in the foreground is holding himself up on crutches. But most of the children in the photograph are laughing. One boy is laughing so hard that his eyes are closed, and he is holding his belly. Maybe the boy is not injured at all, and the children are merely taking turns playing with the crutches? The children’s boisterous joy contrasts sharply with the destruction around them, and the hole in the wall through which we witness the scene.

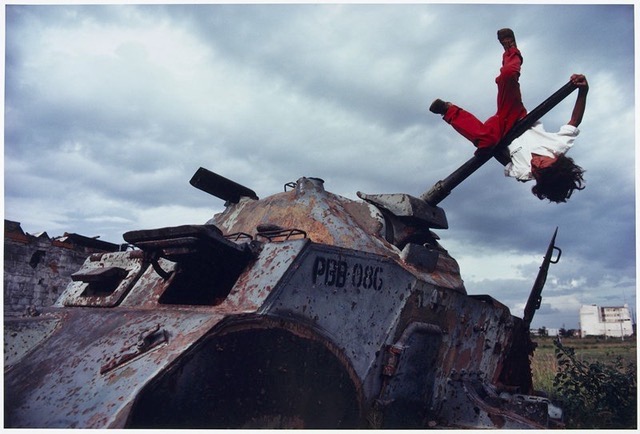

James Nachtwey’s photograph captures a child swinging on the turret of a war tank, transforming a tool of destruction into playground equipment. A military tank, fighting in a civil conflict rooted and financed by faraway powers, loses its power through the simple play of a swinging child.

Play can be painful too. And playtime, at some point, ends.

I write this reflection in the days leading up to the presidential election in the United States of America. In less than one week, the future of the world will be shaped by a small percentage of the planet’s population (4.23% according to Worldometer). These are dramatic words, but in the spirit of play, let’s exaggerate. Or is it an exaggeration to say that the economic and military policies of the United States affect people worldwide?

Let’s play the game of 20 Questions. The goal is to ask yes-or-no questions to reveal the right answer:

- Who writes the rules?

- Who benefits most from the rules as they stand?

- Who is allowed to change the rules, and when?

- Who wins?

- Who trusts the election process?

- Who will believe the results?

- Who gets to vote?

- Who gets pushed to the sidelines, and why?

- Who does the pushing?

- Will the rules be followed?

- Who enforces the rules?

- Who doesn’t play by the rules?

- Who is punished when they break the rules?

- Who suffers the consequences?

- If your land is destroyed by weapons made and supplied by the United States, don’t you get a vote?

- Why are billionaires building underground bunkers and compounds?

- When will we stop shattering records of droughts, floods, hurricanes and heat waves?

- Can the natural world survive our inaction?

- Can humanity go on like this?

- Who will not participate in a game they always seem to lose?

I am terrible at this game. I never seem to ask the right questions, so I never find the answer.

Play can reveal power imbalance. One person’s play can be another person’s trauma. Anyone who has ever been a victim of a playground bully understands power imbalance, and the physical threat resulting from facing a bully and their friends. Bullying is a familiar trope in books and films, spanning genres from comedy to horror to feel-good stories. Unfortunately, some bullies never grow out of their tactics, and we too often see them in leadership positions, using the same methods to silence or punish anyone they don’t like or agree with.

Play teaches equity. We learned to protest “it’s not fair” when someone cheated during play or got an advantage that allowed them to more easily win. We learned about winning, losing, and being left out when no one picked us for a team.

Through play, we can transform reality and imagine new worlds. Art does this too. Artists use trial and error, experimentation, curiosity, and a deep understanding of the rules - and knowing when to break them. Artists nurture the work in progress, adapting, questioning, evolving, and playing. Through art, we invite others to join the game, and to invent new ways to play.

Lessons from the playground (adapted from All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten by Robert Fulghum):

- Share knowledge and resources: Let go of deficit mentality. Think creatively. Learn to use the resources available. Learn and educate.

- Clean up your mess: No one should have to clean up after everyone else. When possible, leave things better than you found them.

- Play fair: Acknowledge inequities and work to dismantle systems of oppression. In life, we don’t all start at the same start line. Don’t keep changing the rules to favor the same people.

- Don’t hit people: Not with words, fists, bombs, or bullets.

- Apologize: Say you’re sorry when you hurt someone. Act to stop cycles of harm.

- Play: Ask questions, make mistakes, be silly. Dance, think, draw, and wonder “what if.

- Take turns: No one likes having the same leader all the time. Give someone else a turn. Vote for it.

The game is called How Do We Save the World. Who is ready to play?

Let us listen to the elders

Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Lakota, Kiowa, Pawnee, Ute

And the other 42 tribes that live in Colorado

Who remind us the planet is as much a relative as a resource

If you are in this room recognize this

Heal Colorado to win, win to heal Colorado

Operating as an ecology over an economy

Find out why abuelo embellishes about his ranchos

Where he found tia frijol y calabaza

Biodiversification means humanization

Don’t you know being in rooms with folks only like you

Is a metric of monocultures

Where are the songs for the seasons

I cannot hear any drums anymore

I dream of deafening songs from cranes

Sanctioned marched of tarantulas

Wandering wolves and stable farming

We can’t keep favoring two leggeds

Haven’t you been on tik tok

Kids got podcasts wandering swamps and plant foraging

Pronouns intros, Southern, East coast

And an un-inimitable Albuquerque accent

America panned the camera

Showing folks of all kind benefit outside

Generations of hunters, canoers and birders

Any good field ecologists observes

These youngins are acting different

They’ve been listening despite our bias

Purifying water, legislating and direct actioning

A spunk just like my Mexican grandparents

The elders remind us

Mitakoye oyasin

All my relations

The siblings that flow, layer and precipitate

Climbers, guides and conservationists

Educators with headwater knowledge

A biodiverse ecosystem of mind, bodies and souls

Stewarding generations of two legged and four

Brother pike, sister corn, cousin pika

First nations practices cause we going back to them anyway apparently

There’s a lot of spiritual fine tuning left

Get into that mechanic shop heart you got

When you can’t recognize the tools anymore

Remember homo habilis hacked tools up too

Mycological hominids

Epigenetic spiritual advice

Keep the young ones close to Tonanztin

Mother of all sand dunes, rockies and prairies

Conserve the love soil cantos

Any native person knows mother’s worth everything

Why else do run backpacking trips

Prefer herds in green pastures over factories

Fish where the surfactants don’t touch

Camp beyond light and sound pollution

Litigate for legends our grandparents dreamed about

Ascending the prayers for acequias

Facing doubts of democracy and profit

Heal generations of broken promises

Listening to pebble, plant, pond, people stories

Nature doesn’t show everything to everyone

Scar stories cause is wise to learn

Discerning the times we cut in, extract or exploit

Our consumption, bills and responsibilities are man-made and ours

Give native and frontline people your money

Risking reputations and cold shoulders for justice

Redirecting boards, trusts and friends

Freeing waters who miss families in the south

A parade of ribbon skirts and drums return to the forests

Remember its for the sake of us all

Colorado the beautiful is our initiative

Listen to the elders

Nature is home

Colorado means colorful

I wonder what name it had before

I wonder if we heal if we can remember

I wonder how many names it has had

The elders remind us we’re an ecosystem

I bet you they have the names

I wonder if we’ll heal enough

Just to remember

What the elders said

Pay artists

Period?

Yea, period. Pay artists.

But, I am an artist before you cut the check.

Remember that.

Just like a tulip is a flower before their beauty makes you break your neck and cut the stem and take them home where you share their essence with your friends.

In fact…

I am an artist because I chose to open up and stop caring about your love and started choosing

myself while I send most opinions to hell.

I mean, I have my collective,

I have my people I manifest with,

We should probably be more protective,

But many of us are givers, you see.

Folks witness us pour out and they want to take our seeds.

Some to sow them

And others to deny posterity.

Yet, I’ve learned the sky provides and my roots will have plenty.

So even in a drought, I will always have what I need.

But you should still pay artists,

Yes, pay me…and pay me well.

How is this still a topic?

Why do we not yet believe?

I take the shit from life, feed the earth and produce giving-trees.

Hungry souls pick the fruit, turn into gods and oft forget

The beat, the word, the brush stroke that awakened their deity

Hmm…

Maybe I should stop taking shit.

Hey artists, maybe we should stop taking shit.

That’s why we write and why we sing and why we paint hoping they’ll get it.

We speak louder, we reach farther, wear our dreams in public.

Folks think it’s crazy until we’re like Basquiat…

Started off as vandalism while gentrification creates mural fests.

So I repeat, cut the check.

Artists are the teachers so pay us…

Wait, y’all don’t even pay them.

Okay,

Artists are the healers, the doctors, the therapists.

Artists break the molds, we pay attention to the “accidents,”

We let failure transform us and transform our world: butterfly effect.

And, real quick, let’s address this:

Art transforms even if aesthetes aren’t around to witness it.

Because if the artist is changed, so is the world they live in.

Let that sink in.

That’s my contribution: a better me.

Artists discover life’s derivatives, call us mathematicians.

We step inside rips in the continuum and come back more than human.

Writing, painting, sculpting…hopefully en-light.

Folks think we’re crazy until death proves us right.

It is too often that creatives are overlooked on park benches; we need post-mortem advances.

Pay us while we are alive.

Pay us in the present.

Pay us in the moment.

Pay us until we kill the blasted term “starving artist.”

Pay us, at least, until we completely transform the system,

Until we reach higher grounds by sharing our inner visions,

Even Stevie Wonder saw it and named it…expanding senses, breaking limits.

Pay us for breaking limits.

Pay us for doing it different.

For those of us that survived hell-like conditions,

Pay us for living.

Pay us for telling these tales so that you could feel something.

Pay us for feeling it first.

And although many of us think to change the world, creating worlds that we deserve, creating

worlds that hold up mirrors…this is our world.

A beautiful tragedy:

Wars and the artists that cry out against them, freedom and the supremacies created to deny

them, slave trades and doors of no return, reclamation of roots while books and forests burn,

rhythm and poetry that fight the powers that be, greedy souls that rather move to Mars than pay

their employees or for peace.

We are…indeed…a beautiful tragedy…

And will likely remain to be.

But I thank the gods that I am an artist that will shine love from my chest.

My throat thick with hope because I will not be bested.

I will write and will write so that the children never forget,

And I will be paid for this sacred light.

That’s on periodt.

This piece is offered as a response to the Tilt West guided conversation of May 14, 2024: Art in Public Space: Permission and Freedom. I have avoided direct quotes for fear of mis-quoting, mis-attributing and mis-contextualizing and so what you are reading are my own reflections on what I heard and my own contemplations on that conversation and its subject matter.

I don’t consider myself an artist in that I don’t generally create works that are designed or marketed as art. I do design and implement interventions in the public realm, and these interventions are all designed to provoke a certain response in the viewer, the passer-by — the user.

So while I find myself asking, what is the difference between what I do and Public Art, I’m not sure that’s really an important question. Instead, I find myself questioning what it is that brings together such disparate forms of work under that singular, specific umbrella. Whether we’re talking about graffiti, municipally commissioned and high-budget expressions of civic pride, or developer-bought murals, we’re calling all of them, broadly, public art — with an emphasis on Public.

I’m not sure I believe the creator of public art who tells me that they are doing this for themselves, that they don’t care who the audience is. If the creation is just for yourself, if the audience is irrelevant, why is it in a public place? If the observation of that art wasn’t, at least in some way, part of the point, why does that art ever leave the creator’s basement? Why not paint their own living room walls instead of very intentionally placing their art in the public realm?

What is public art? The City trying to leave convention visitors with a memorable experience — an Instagram-able moment that might prompt them to return. The property-owner communicating to the local graffiti-makers that this wall is no longer available for their musings — and to potential tenants that this neighborhood may be edgy, but it is safe. The frustrated youth who sees that mural as a sign he is no longer wholly welcome in his own neighborhood expressing that frustration by tagging it. The community development agency trying to reassure community members that they still have a place in their own community by commissioning culturally- and place-relevant work. Others signaling who is welcome and who is not — a marking of territory by an American street gang member or a Belfast militant.

We have, in Denver, a few examples of very fine public art which is not visual, but auditory. But isn’t the official sanctioning of (auditioned and approved) buskers simply the auditory version of a municipally-commissioned mural? And perhaps the car with a sub-woofer that makes nearby vehicles shudder in rhythmic harmony is the auditory version of tagging? A statement to passers-by (or those passed by) that I am here and I demand to be seen (heard).

The work may vary, the creators and commissioners of the work may have vastly different intents, but what these all have in common is that the audience lacks agency. Going to a museum or a gallery is a self-selecting activity. Seeing, or hearing, public art is not.

I posit that the commonality, what defines public art, is an unwilling viewer.

That doesn’t mean the viewer necessarily dislikes what they see, though they might. That doesn’t mean that they don’twant to see it — they might. And, yes, some viewers might come to a place to see a specific piece of public art, but by and large the viewer comes to a place for a reason other than seeing the art in question and is confronted with it.

Whether in a museum, a gallery or a private collection, art that requires the viewer to enter a space to view it becomes subject to a tacit understanding between artist and audience. Work that is challenging, even confrontational, is still subject to that understanding. The viewer has given their permission to the artist for the exchange. The artist, in return, has created art they expect to be viewed or experienced within certain parameters of control.

Public art, on the other hand, has no such contract. There may be a target audience, but those viewers have no say in the matter. Nor, of course, do the other bystanders who may be but the art equivalent of collateral damage.

That is not to say there aren’t agreements around public art, sometimes explicit ones. These could be the understanding between the makers to respect, and not tag, each other’s work — or the contract between a commissioner of public art and the artist, spelling out payment, placement, and often content. But there is an intent on the part of the artist or commissioner to impose something on the viewer, and without their permission.

That intention drives the art itself, shaping its form, its placement, its message.

Why do we make memorials? We want people to pause in their day to remember an event, a person. We want them to take a moment to remember the youth killed by gun violence. We want them to remember the great deeds of a great leader. And in some cases, we want the viewer to be confronted by things they might rather forget, whether that is the losses of war, as with Maya Lin’s remarkable Vietnam Veterans Memorial, or what their own place in society once was, as with the Confederate memorials which still stain so many Southern cities.

The developer who commissions that mural looks for the artist who helps to complete the brand. Edgy, but safe. Exclusive, but still authentic.

The tagger’s bravado in scaling a bridge earns the admiration of their peers. Their defacing of the developer’s mural earns the developer’s scorn, and just maybe the admiration of fellow victims of cultural and physical displacement.

Public art may have many different ambitions — to bring joy, to provoke, to memorialize, to gain recognition — but it is by definition a public act, a public statement of our presence, our ambition, our love, our pride, our anger. What could be more transgressive than imposing our own vision on others?

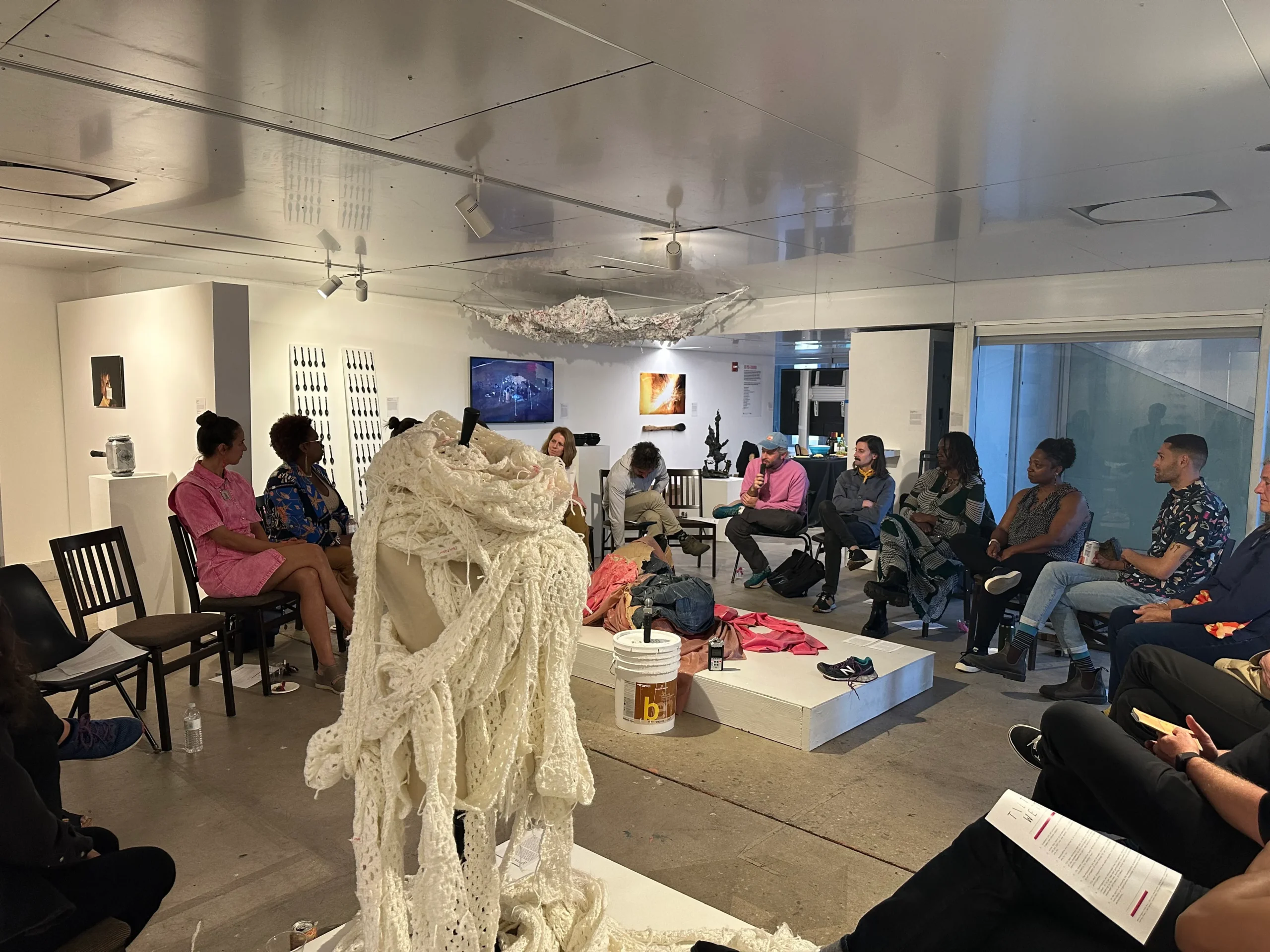

Against the backdrop of the Denver Botanical Gardens exhibition, Indigo, Tilt West’s September roundtable participants passionately discussed the intersection of Art and Craft through the lens of Equity, Representation, and Contemporary Politics. Prompter Rebecca Peebles brought years of exploring repetitive, meditative practices rooted in craft for creative and contemplative ends to the conversation. Resources provided before the discussion featured leading contemporary artists using craft practices to dissect the complexities of our modern world. As Peebles asserted in her written prompt for the event, “Craft artists and aesthetic thinkers must now courageously put their hands and hearts back into the work of defining art.” [1]

One theme united the conversation: the concept of craft being “radical.” Peebles, for example, embodies radical approaches to her art and healing. Roundtable participants discussed radical acts of personal and communal well-being; notions that radicalism lies at the heart of craft, which is the revolutionary foundation of our daily lives through hands-on engagement; and the intrinsic radical nature of craft itself.

In his introduction to Radical Lace and Subversive Knitting, the catalog for a 2007 exhibition at the Museum of Arts & Design, David Revere McFadden asks, “How does something as innocent and harmless as knitting become subversive? How can lace serve radical ends?” [2] This exhibition showed the transformative power artists have through traditional craft techniques. The familiarity of these techniques creates an accessible entry into work that gradually reveals radical content, such as calls to action and visions for a better future.

One artist from this exhibition, Cal Lane, used a plasma cutter as her needle and thread to cut elegant lace patterns in steel car hoods, connecting the history of labor-intensive craft to the mass production of the contemporary automotive industry. “Lane’s work is paradoxical: feminine and masculine associations play against each other; the techniques of industry and handicraft meet; delicate designs overtake durable materials; and positive and negative spaces create a beautiful play of light and shadow merging the high art connotations of sculpture with the aesthetic of craft.” [3]

For roundtable participant Heather Schulte, an interdisciplinary artist based in Colorado, craft transcends cultural and ideological boundaries, offering a common ground for new frontiers of artistic language. Schulterecently discussed the intersection of personal and public forms of language and communication with the Textile Society of America. “I also see textiles as a form of text, as they hold within them the stories of both the animals or plants that are the material and the humans who create new items with said material. Across history, they have also been used as storytelling devices, from quipu knotting systems to medieval tapestries, subversive samplers to contemporary quilts. I draw upon this rich history and utilize modern forms of coding to embed my stitches with messages and commentary on the issues of our day.” [4]

Other participants in the Tilt West roundtable included artists, crafters, musicians, a coffee barista, an avid gardener, and a museum curator aptly named Hannah Craft. All shared personal experiences that supported this unique, organic conversation while exploring craft through the eyes of equity, representation, and contemporary politics. A simple Google search of equity + craft yields 115,000,000 results. As Peebles’ opening statement mentioned, “Artists today are using craft media to claim the variability, diversity, and intersectionality of personhood expressed through creative practice.” [5]

Craft platforms today address equity in their mission and vision statements as an impetus for change. One craft council wants to foster “livelihoods and ways of living grounded in the artful work of the human hand”while using craft as a catalyst to “draw on the rich legacy of openness and its deep roots in all cultures.” [6] Another international craft forum intends to “Foster awareness among people in the arts globally to prevent our artists from being perceived as artisans rather than true artists.” [7] and to “connect Black craftspeople to the power of place.” [8]

As the discussion continued, roundtable participants challenged the use of labels that tend to separate craft from art and craft artists from fine artists. Setting aside the endless debate of whether craft is “high” or “low” art, one might consider the Four C Model of Creativity researched by creative psychologists James Kaufman and Ronald Beghetto. Grounded in the belief that there is no hierarchy in creativity, the Four C Model of Creativity identifies varying levels of fluid creativity. Little-c creativity, or everyday creativity, includes songwriting, inventing new recipes, or decorating a room. Big-C creativity, or genius creativity, has a broader impact and is often associated with the culmination of work from publications to exhibitions. Mini-c creativity, or personal creativity, refers to new and personally meaningful interpretations, ideas, and insights. Pro-Ccreativity, or expert creativity, describes individuals who have reached a professional level after years of experience and training. [9]

This model helps people overcome the idea that they are not creative if they don’t fall into the Big-C or genius creativity category. An example of this is someone believing they are not creative because they can’t sing as well as Beyoncé. [11] The Four C Model helps expand the idea of creativity. Whether you are making a significant impact on society or making Thanksgiving dinner, everyone makes creative contributions to the world. Educational psychologist Dr. Ruth Richards reminds us that everyday creativity “is not only universal but necessary to our very survival as individuals and as a species.” [12]

As the character of Madame Defarge states in A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, a skill becomes useful when and where it is needed to effect revolutionary change. In this 1859 classic, Madame Defarge encoded a secret list of aristocrats and enemies of the Revolutionary government in the stitches of her knitting. [13] While many things have changed since 1859, it is evident that our response to using our hands to implement world change has remained the same. Artists continue to harness the transformative radical power of craft and subversive stitch, advocating equity, social justice, mental health, and environmental causes to foster a brighter future.

There we were, about two dozen of us sitting in a circle. Something about the arrangement evoked the feeling of a group therapy session for addiction recovery and in the moment when we were called to take our seats, it was hard not to be acutely aware of the stages my own relationship with various social media platforms has been through. I was ready to share, perhaps I wanted to know that I was not alone. Had we all experienced a similar arc? Innocence and curiosity, professional networking and portfolio building, idle addiction, toxic doom scrolling and shit posting. My palms began to moisten. I’ve never been to an addiction support group and I was beginning to feel not only as though I might need one, but that this was going to become one.

Autumn T. Thomas prompted the group discussion with an observation about the cultural shift in the arts from pre to post internet. Having experienced the evolution from analog to digital networks, Autumn noted that the arts had not been shielded from the culture of accelerated production. If before, art was developed through private reflection and encounters with and within the physical world; today, the artist is in a performative role, responding to simulated experiences, managing the (hyper)creation of work under the expectation of opening up processes, sharing — perhaps before work is ready for public consumption/presentation — and perpetuating a culture of consumption of simulated experiences.

It’s 2023 and social media is a pervasive and ubiquitous part of daily life for a majority of internet-connected humans on planet Earth. The utility of the technology is clear. We can all point to experiences where it has helped make connections, opened doors to new communities, or fostered personal or professional growth. On the other hand, a growing body of research reveals the detrimental effects of social media addiction and its unhealthy use, on both mental and physical health. A few have managed to push it out of their lives, but even then, I have to wonder whether deep down the FOMO still smolders.

As an artist, I understood the prompt for this roundtable as inviting a discussion on the role social media plays, could play, or should play in arts practices. How has social media technology impacted the kinds of decisions artists and arts organizations make regarding how they build their careers or organizations, what they share, how much they share, who they share it with? Considerations such as how much of an investment of time and resources to make in post creation, or how to make sure that you’re reaching your audience, must be weighed against what we can reasonably expect to gain from our engagement and how we wish to feel afterwards.

Social Media As A Tool

For artist-users of social media platforms, these sites function as valuable tools for discovering other artists, finding inspiration, learning new techniques, researching culture, connecting to others, forming communities, starting collaborations and growing networks. For the platform creators, the sites are a lucrative system that harvests vast amounts of data on individuals, profiles and categorizes them, and sells their attention to advertisers.

According to an article published by the Pew Research Center, “A substantial share of websites and apps track how people use digital services, and they use that data to deliver services, content or advertising targeted to those with specific interests or traits.”[1] As Richard Serra put it back in 1973, “If something is free, you’re the product.” Though made in reference to television, the remark remains relevant to social media, which reflects a hyper individualization of the ad revenue model used by television, radio and print media. “The feed” is algorithmically populated with content based on the information we provide to the platforms. It has three primary goals: to keep us engaged with the site (scrolling), to gather information about our responses to the content so that the algorithm becomes better attuned to our preferences, and to use that information to build our advertising profile.

The information gathered comprises the totality of our engagement with the platform, its affiliated services, and code hosted by third parties. This includes information we provide when signing up, the content of our posts, our likes, the comments we leave on other posts, who we follow, who follows us, the frequency we post, where we are posting from, how often we open the app, where we are when we open the app, as well as the amount of time we pause on each item in our feeds as we fall into the hypnagogic state of the perpetual (doom) scroll. You don’t even have to be using the app or even signed in. Sites that have a “share” or “like” button for a social media platform and those that use third-party web analytics are part of a wide tracking dragnet. When your browser executes the javascript that powers one of these widgets, it’s phoning home to the social media site to which it’s connected. Every browser you’ve ever used to access your account has its own database entry held by the social media platform and is used to continuously correlate your activity.

A member of our group suggested that social media, as a tool, was akin to a hammer. Another suggested that to complicate the analogy, imagine that this hammer was addictive. Now imagine that the hammer is also watching you, learning your preferences and using what it learns to place things before you that you’re most likely to hit with it. When we use these platforms, we relinquish a degree of our power, control, privacy, anonymity and autonomy. Yet despite the power held by those who designed these systems, they are not totally within their control. Though these platforms are now complex, engineered systems of algorithms aimed at shaping individuals behavior for commercial gains, they will always be more than what they are intended to be. They have their own inherent properties and may behave in ways that run counter to the goals of their creators.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as vaccines were being developed and approved for emergency use, Facebook made a concerted effort to promote them. But anti-vaccine activists flooded the network with “barrier to vaccination” content, using Facebook’s own tools to sow doubt about the severity of the pandemic’s threat and the safety of vaccines. Despite Facebook’s intent to use its own tools for public benefit, Facebook’s algorithms were exploited to do the opposite.[2]

This example highlights the degree to which algorithms and designed systems possess power independent of their creators. This machine autonomy is precisely what social media companies harness and shape; the downside is its potential to be harnessed by other parties.

In theory, it should be possible to use social media as a tool, while simultaneously limiting the degree to which we are used by the platforms. How do we shift the balance of benefits in our favor, and sacrifice as little as possible in the process?

A number of us use social media as a means to an end, an activity to compliment, develop or promote practices based largely outside of or independent of the platforms. To approach this activity with intent and discipline is what I consider to be a practice of using social media. While a valuable approach to limiting the extent to which we are used by the platforms, a deeper form of critique and social commentary is possible by approaching social media as a practice. What this entails is using the platforms with the intent of addressing the role they play in shaping culture and society, and using aesthetics and format of the platforms (UX/UI) as material.

Pioneering artists through history have embraced, experimented with, and incorporated media technologies into their practices. Artists working today to address sub-cultures developing on social media sites, who use the platforms as an integral part of how their work is produced or experienced, and who question prevailing cultural trends driving their development continue this tradition. These practices fall under the umbrella of new media art, more specifically extending net art into the age of social media.

While not a central or necessary feature of new media art or net art, critique features prominently in much of the work that takes its own conditions and circumstances as its subject matter. This self-reflexivity as a critical perspective is a powerful tool to question, push back against, or draw attention to uncomfortable realities that may reside just beyond our field of view. The following three projects are examples from social media’s early years that leverage social media as a practice to engage in self-reflective cultural critique.

The Jogging: Aestheticism and Compulsive Consumption

Liking a post sends a little dopamine hit to its creator, who then seeks the next hit by creating more content and sharing. The more we share and engage, the more we share and engage. We all keep coming back for that hit in a self-reenforcing cycle. Consumption and creation become compulsions when performed on and for platforms engineered around addictive use.

The Jogging is a Tumblr blog created by Brad Troemel and Lauren Christensen. It was started in 2009 as a direct response to the emerging culture of social media and how it was transforming artistic practices. Rather than oppose the hyper productivity and creation/consumption spiral, The Jogging leans into it.

“The name ‘Jogging’ refers to a work flow,” Troemel says. “Constantly moving, and not really focusing on any one thing, but rather to just continue forward.” This always-on approach means practically everything is a potential creative prompt that can be acted on immediately; Troemel has called this athletic aesthetics — the practice of the “aesthlete.”[3]

Excellences and Perfections: Performance and Reality Making

In 2014 artist Amalia Ulman conducted a scripted, months-long performance on her Instagram account, taking aim at toxic cultural practices supercharged by the democratization of image-making and the desire to project success and wealth by reproducing a luxury consumerist fantasy. “As part of this project, titled Excellences & Perfections, Ulman underwent an extreme, semi-fictionalized makeover.”[4]

Using her own personal account, she leveraged the inherent difficulty in separating fact from fiction on social media platforms to such effect that her closer friends oftentimes confused Ulman’s social media performance for her lived reality. This confusion highlights the way fictions promoted on social media platforms produce their own reality, one which has the power to shape our lived reality.

Her critique is subtle but deep. By embracing the cultural logic of social media and taking it to its conclusion, Amalia was able to draw attention to the imbalance in power that persists despite the democratization of image-making and self-publishing, and the degree to which we’ve internalized and reproduced ideals shaped by a wealthy elite to project fame and success — read: the culture of celebrity and perfection.

Escaping the Sandbox

“In computer security, a sandbox is a security mechanism for separating running programs, usually in an effort to mitigate system failures and/or prevent software vulnerabilities from spreading.”[5] A platform’s interface–the graphical elements, font, page layout, and its overall design, both visual and functional–are analogous to the interior design and architecture of a building. The design establishes an atmosphere, or mood, or vibe, if you will, while also signaling how we should navigate a space or platform. User flow and site functionality create permitted and prohibited behaviors. In this way, the UX and UI of social media sites sandboxes users, dictating through the logic of code what can and cannot be posted and how posts will appear.

Glitch art is a subgenre of digital art that encompasses a range of practices concerning errors and artifacts in systems of logic. Early glitch art (pre-2012s) featured artifacts from systems where the data being displayed on screen had become corrupted. What was discovered through chance encounters quickly became the goal of intentional interventions. By exploiting the fragility of digital systems to achieve outcomes unintended by the system architects, glitch artists became akin to computer hackers.

Glitchr’s work on Facebook leverages flaws in the code of the platform to work with the platform’s fundamental design elements and user interface as expressive media, effectively opening doors in the platform’s walls where there were none before. He blurs the line between artist and hacker and in doing so is able to manipulate the frame Facebook places around all content posted to it. By drawing attention to this frame, and oftentimes filling it with incomprehensible unicode gibberish, Glitchr invites us to consider the control that platforms have on shaping our content and the ways in which we express ourselves, and the degree of technological virtuosity required to break free of this sandboxed environment.

“In computer security, a sandbox is a security mechanism for separating running programs, usually in an effort to mitigate system failures and/or prevent software vulnerabilities from spreading.”[6] A platform’s interface–the graphical elements, font, page layout, and its overall design, both visual and functional–are analogous to the interior design and architecture of a building. The design establishes an atmosphere, or mood, or vibe, if you will, while also signaling how we should navigate a space or platform. User flow and site functionality create permitted and prohibited behaviors. In this way, the UX and UI of social media sites sandboxes users, dictating through the logic of code what can and cannot be posted and how posts will appear.

Glitch art is a subgenre of digital art that encompasses a range of practices concerning errors and artifacts in systems of logic. Early glitch art (pre-2012s) featured artifacts from systems where the data being displayed on screen had become corrupted. What was discovered through chance encounters quickly became the goal of intentional interventions. By exploiting the fragility of digital systems to achieve outcomes unintended by the system architects, glitch artists became akin to computer hackers.

Glitchr’s work on Facebook leverages flaws in the code of the platform to work with the platform’s fundamental design elements and user interface as expressive media, effectively opening doors in the platform’s walls where there were none before. He blurs the line between artist and hacker and in doing so is able to manipulate the frame Facebook places around all content posted to it. By drawing attention to this frame, and oftentimes filling it with incomprehensible unicode gibberish, Glitchr invites us to consider the control that platforms have on shaping our content and the ways in which we express ourselves, and the degree of technological virtuosity required to break free of this sandboxed environment.

Shifting Sands Call for Nimble Feet

Today, something has changed, but I can’t quite put my finger on it. All of the projects presented above have gone silent, their last posts made in 2014. Of course, in the time since, there have been several public and controversial changes to the algorithms of platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr as well as changes of ownership and management. Whole new platforms have emerged, like Tik Tok, which isn’t much different in that it makes its money mostly through advertising[6]. Largely, what has remained unchanged is the presence of social media platforms occupying the center of our lived experience on the internet.

So what happened to the creation of critical work about social media on social media? Has the noisy culture of viral celebrity fame drowned out the subtler forms of critique? Have the algorithms, whether by intent or by consequence of their internal logic, simply ignored the potentially ambiguous content? Is it that our culture as a whole has changed, warped by these very social media technologies so that we no longer have the capacity or patience to register works that ask more from us? I refuse to believe that artists have altogether given up and simply gone along unironically with the internal logic of these systems. Perhaps they’re flying below the radar, or are in plain sight. What I know for sure is that the algorithm does not appear to be serving them up to me.

The platforms and their revenue models have been with us for so long at this point that they feel as though they will inevitably persist into the foreseeable future, at least until something new replaces them. However, their algorithms will continue to evolve, augmented and extended by technological advances, mutated and permuted into new forms. As we in the arts wrestle with the role of online technologies in our practices, it will be vital to take up critical positions if we hope to push back or develop alternatives. Perhaps another reason why the critical work eludes me is that it simply isn’t productive to shout about the void into the void, and the more productive route is through direct political action.

“Once you start approaching your body with curiosity rather than fear, everything shifts.” –Bessel Van Der Kolk

“When did you become aware of being embodied?”

This was one of the first questions posed by Donna Mejia, who co-prompted Tilt West’s March roundtable discussion, The Body as Medium: Somatics in Creation, with Charlie Miller. The participants’ responses had a consistent theme: the moment of embodiment was often the instant when people became aware of their bodily suffering or their difference from others. Awareness came when what had been invisible or imperceptible suddenly became loud and unmistakable, brought about by immobilizing injury or a long bout of illness. Does this imply that we are almost unaware of our bodies before such a moment? Are we merely sensing beings, incidentally in a body we’ve not had to think about? Ironically, being forced by pain to perceive one’s body as an “other” suggests a contradiction: before this point, while we are blissfully unaware of pain–and by extension, our bodies–in our ‘ignorance’ we are probably the most embodied we can possibly be. In other words, perhaps the less you know (of your body), the more you just *are* (embodied). It is when we become aware of this body, and aware that we inhabit it, that we are faced with answering the question of what exactly that means. If we are aware of being embodied, what then are our bodies telling us that we never before had the impulse to question?

Movement, it turns out, is the original communication, both in human history and human development. It arose before spoken language in prehistoric times [1], and it’s the primary language we have from our time in the womb until around age two. Before we learn words, everything we know about the world is processed as bodily sensation, and much that we express is conveyed through movement. During this small window, our perception of self and our physical experience are one and the same. In his famous declaration on thinking, Descartes unwittingly destroyed the validity of such a fundamentally intuitive way of perceiving the world by positing, “I think, therefore I am.” Five hundred years later, perhaps Descartes’ edict bears re-examining, given that he set humanity on a new path in terms of how we understood ourselves. Where would we be if he had offered instead, “I feel, therefore I am?” And what are the implications of this so-called Cartesian split? In exalting the mind while relegating the world of the body to the primal, we inherently lost connection with our bodies. It follows inevitably then that in this separation from the physical we have come to view our bodies as mere vessels for labor, capital, and worse. We have become distant relatives to ourselves, knowing our bodies more through the eyes and judgments of others than by our own sensations.

Shaping Our Bodies to Fit

As roundtable participants discussed their experiences of their bodies, there seemed to be far more than the 30 identities in the room; the chimeras of the ideals and disappointments everyone attached to their bodies hovered like an additional cast of characters. People spoke of estrangements, reckonings, negotiations, and reconciliations with their bodies — all distinct moments along the deeply human journey of squaring our identities with our senses of our bodily selves.

When the question was posed, ‘“What does embodiment mean to you?” many seemed hopeful about reconnecting their identities with their bodies. It struck me that this yearning for self-connection is universal; we are all trying to make sense of the multiplicity of co-existing narratives we have developed around our bodies. Within each of us, there are at least three conflicting scripts about our bodies taking place simultaneously: the story we tell ourselves about our bodies; the story about ourselves we tell the outside world by adapting our bodies; and the dream of finding our true selves in acceptance rather than adaptation. As people shared honest revelations of how their bodies were manipulated by outside forces — allowed to be or not; accepted or not — a tangible sense of openness and sincerity emerged. One by one people spoke of what had been silenced within themselves in order to accommodate the demand that their bodies conform, and how the pressure to change their bodies had often come as much from them as the outside world. That this overarching theme of bodies co-opted emerged so clearly was poignant, yet stark.

What have we sacrificed in order to pursue the agenda everyone else has for our bodies? In this schism, there seems to be a deep, shared sense of loss, yet an inability to disengage from a view that the body is a project. We sense this loss, but can only respond with the impulse to fix ourselves: our bodies are projects to heal, judge, make sense of, and remodel, or they are a nemesis of physical pain, imprisonment, and betrayal. The idea of embodiment, though idealized as a blissful unification of one’s familiar identity with one’s physical bodily experience, seems to bring with it a less beautiful truth. Unification of the psychological and physical means that pain hurts every part of us, un-delineated. In fact, many described that it was when they tried to silence their physical pain, and thus control it through sheer cognitive willpower, they felt alienated from themselves. We can no more imagine that suffering ends at the boundaries of our cells than that psychic suffering resides only in our minds; to do so erases the memory and voice of the body. When we only see our body as a physical vessel to transport our true self, it becomes a second-class citizen more easily oppressed by ourselves and others. Likewise, if our disembodied mind is left to process suffering in isolation, we come to believe we are only amalgamations of our thoughts. Embodiment, sometimes painfully, reminds us all: the mind cannot unilaterally think its way into well-being.

In my experience as a dancer and choreographer, the realization that I could be estranged from my body –separated from myself and ‘me’ as I knew her– came suddenly and unexpectedly. This new separation caused just such a collapse of spirit; a separation not only from my body but from an ideal for it I had vigorously maintained but never experienced losing. The environment of the dance world in which I grew up is characterized by demands of perfection, beauty, and virtuosity, and I shaped myself to fit the mold without foresight for how this might hurt me later. Every part of my worth bending to fit this world was a performance — a performance of conformity to directors and other dancers, a performance of flawlessness to the audience, a performance of ceaseless discipline to prove my worth to myself. I have been dancing professionally for nearly 20 years, and have reached expert status in adapting my body as a project to fit standards of perfection I didn’t make but definitely bought into — especially when meeting those standards afforded me my career. Inherent in using your body for art is the daunting truth that its value is determined by the subjective whims, desires, and aesthetic tastes of others. What, then, were my options if my body ceased to fit into this sliver-thin definition of success and artistry, in small ways like turning older than 33 (how dare I?), or in more formidable ways, like fracturing my spine? The only version of myself I knew was a dancer, and ‘dancer’ had one rigid and unforgiving definition rooted in physical perfection — which I suddenly found myself unable to produce. The disembodied fall from my sense of who I knew myself to be, both physical and existential, was much farther than if I had never so adeptly adapted myself in the first place.

Being With What's So: An Act of Personal and Social Justice

What I came to realize (and what so many in the room at Tilt West’s roundtable described) was that in order to come home to my body and find my core body identity rather than conform to an imposed one, I could no longer negotiate an agenda with my physical self. In the brilliant words of one participant, I had to “be with what’s so” — to be with the pain, the changes, and the matter-of-fact, present state of my body. I had to "inhabit my body from within." [2] As a performer, the urge for theatricality called to me even in this most personal of projects: coming home to my body. I decided to rewrite the directions of performance and use my dramatic skills to take back my body instead of constantly offering it to others. Lying in the MRI machine, rather than succumbing to the dread of the circumstances that brought me there, I performed the most beautiful solo of stillness the world had ever seen, for myself and myself alone. Never had there been such poetic stillness! This playful experiment was a serious attempt to reclaim what first drew me to performance while also honoring its real and deep impact in my life, both painfully and creatively. To take back performance would mean I had subverted the very system that had played a role in hurting my body; the weapon that wounded me could be reclaimed as my tool to find myself with physical presence.

This experience brought me back to the dilemma of peering from one’s intellect at one’s body like an object — when you’re trying to repair connections with your body yet still viewing it as an ‘other’ (albeit one you’ve decided you should be nice to), you stay separated. Perhaps what makes it so hard to accept pain in our bodies is that we’ve lost sight of this simple truth: that our minds are our bodies; they are one and the same. Pain runs through our brains, hearts, and mass equally, and even a practice of ‘mindfulness’ offers only the mind to be with the body. What if we could practice bodyfullness, a term coined by somatic scholar Christine Caldwell [3] as a pushback against the limitations inherent in ‘mindfulness,’ which is rooted by its very name in the mind? In being bodyfull, we might reclaim the body’s role in generating meaning and purpose and understand this as an end unto itself. As Caldwell describes it, conscious sensing, breathing, and moving might be seen as a form of bodily prayer. We might be with what’s so, listening within just to hear, looking just to see, feeling just to feel, being with — just to be with. Co-prompter Donna Mejia described her own way of engaging with this idea of being bodyfull as a sort of companionship she found with herself, based on her revelation that ‘your body can’t lie to you.’ When she listened she could hear its truth — or rather, not just its, but her OWN truth.

Being with what’s so is inherently radical. It takes our bodies’ value and function right out of the hands of profit-seekers, employers, societal ideals, and those who oppress and marginalize bodies, and it says our bodies are for ourselves. It shirks somatophobia (the fear and distrust of the bodily self) because if we can be with what’s so, not change what’s so, not judge what’s so, not escape what’s so. It removes the ubiquitous idea that we are projects. When we believe that only our minds are within our capacity to set free, while our bodies stay painfully ensnared, we oppress and cut ourselves off from our wholeness. We liken our bodies to jails; thus becoming unknowing accomplices to our culture’s figurative and literal incarceration of bodies, whether from suffocating beauty and aesthetic standards or actual bodily imprisonment. Accepting our bodies as ourselves through our felt sense of them, rather than othering them, allows us to challenge social structures and oppressive ideologies that seek to make claim on them. It empowers us to experience the world differently despite such ideologies [4].

Being with what’s so in ourselves, then, is not an intellectual truce with our bodies; it’s describing who we are to ourselves by way of sensing as much as conceptualizing. ‘Coming home to ourselves’ might reveal that our deepest identities are ours and ours alone, out of reach of any force that might construct and impose identities to take away from our own. This was captured poignantly by one participant, who detailed the experiences in her body following a traumatic car accident that led to a brain injury. After the accident she would enjoy periods of dissociation whereby she felt she left her body and had visions, a gift of escape from her physical suffering. Suddenly one day this rare side effect disappeared, and she was left to stay in the physical dimension filled with significant pain in a body whose movements she could not control. She had no other option than to ‘be with what’s so’ (in fact those were her words to describe it), yet it was here that she found her most profound spiritual growth and grace. Here she touched her deepest identity, in its fullest, and carried on not despite but WITH everything that was.

When I practice creative bodyfullness, I wonder if I’m looking in on my new form of performance with my own eyes, or if I’m being tricked and am still seeing myself through the gaze of outside judgment (the Great and Powerful Oz that is the ‘dance director’ looking through me). But there are signs that it’s me performing for myself and no one else. There are things that come out of me so intuitively they can only be the signature of my unedited core identity, my body imagination, my me-ness — my mind, body, and soul as just one expression through the medium of my body. When I listen without judgment, conclusions, or even friendship as an impulse, and just allow myself to be with what’s so, I know I’m there with myself. The signature is everywhere: from the innate voice that always comes out in my choreography, to the spontaneous melodies I hum while doing dishes, to the idiosyncrasies of my bodily form, which somehow carry the same essence of ‘me-ness’ made corporeal. I couldn’t invent this signature if I tried (in fact *trying* to be authentic has failed spectacularly, especially when making art). The real art of coming home to the medium of the body is in listening with the heart and not the head. While our brains may process our pain, our hearts emit the strongest electromagnetic field in our bodies, 5,000 times stronger than the brain [5]. Perhaps we might tap into this current not just as a pulse but as a powerful source of knowing ourselves beyond the concepts created by our brains. Maybe Buddhists have the antidote to Descartes’ division–they consider the heart to be the center of human perception. We can use our compassionate hearts to be with ourselves — we have the wattage to do it.

In November 2022, Tilt West’s roundtable convening took ‘Artist Collectives and Collaboration’ as its topic. Over the course of the discussion, we mused on foundational aspects of collectives and collectivity: critical definitions of their function and role, the types of power they hold, and the benefits or risks they could yield. Being a fresh Denverite, I was grateful for the rootedness of the discussion in local collectives, past and present. Participants included artists and members of collectives, co-ops, and collaborative projects, such as isPress, Denver Digital Land Grab, and Mo’Print, among others. The resulting meditation on collectivity was situated in personal experience and knowledge.

The conversation began with a parsing of definitions: What constitutes a typical artist collective? Are formal membership, hierarchy, or organization necessary? These questions, posed by co-prompters Anthony Garcia and Raymundo Muñoz of Globeville’s Birdseed Collective, reflected a desire to identify the nature and potential of collectivity within the artistic and cultural realm. As practicing members of a collectively run organization, Garcia and Muñoz spoke from firsthand experience of wanting to amplify the impact of their individual work as artists by working together to engage the non-artist community. True to its name, Birdseed Collective, founded in 2009, endeavors to collectively plant the seeds for a thriving community, functioning as an “outreach organization that is dedicated to improving the socio-economic climate of Denver, Colorado through innovative arts and humanities offerings.” Birdseed follows in the footsteps of other community-focused, collectively run cultural organizations in Denver like Chicano Humanities and Arts Council (CHAC), which was founded in 1978 by a group of visual and performing artists. CHAC began as a place where Chicano/Latino artists were provided with a venue to explore visual and performance art and to promote and preserve the Chicano/Latino culture through the expression of the arts. [1] As community supporters and generators, CHAC and Birdseed provide cultural sustenance through collective work and a belief that shared talents, experiences, and resources are stronger than those of individuals.

A Lexicon of Collectivity

So, what constitutes an artist collective? How is it different from or related to other terms like collaboration and cooperation? The inherent flexibility of collective work imbues it with a slipperiness that makes it difficult to define in totality. Perhaps the sense of wholeness derived from being part of a group rather than working as a singular individual is tricky to understand within the capitalistic, patriarchal societies of the western world. To be part of a collective implies a named commitment to a set of shared stakes, shared values, and shared resources. In short, collective work requires the sense of generosity that informs the counter-societal structures mentioned above. Often eschewing hierarchy, collectives propose horizontal organizational structures that distribute and harness power across their membership.

Within an artistic context, collectivity has been defined as a group of artists “united by shared ideologies, aesthetics and, or political beliefs.” [2] The Toolkit for Cooperative, Collective, Collaborative Cultural Works, published by Press Press and the Institute for Expanded Research in 2020, outlines the following definitions:

Collaboration: Collaboration means being a co-author of the work in some way. Collaboration may feel closer to your heart.

"Collective Work: Collective work is a broad term that can be used to describe different types of processes and structures that involve a group of people working together in some way. It may imply a longer-term working relationship that spans multiple projects.

Cooperation: Cooperation is an act or instance of working or acting together for a common purpose or benefit. Cooperation can happen with many people and may include a more hierarchical structure." [3]