Lessons From The Playground

The memory is this: playing on a beach called Bombinhas (meaning “little bombs,” named after the sounds of the crashing waves) in the southern Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. A child about my same age was nearby with her mom, and we start to play together. I could not understand a word she said, and she could not understand me - her Argentinian Spanish sounded like puffs of sounds to me, as my Brazilian Portuguese probably did to her. But we shared a common language: the language of play. We were fluent in beach toys, sand, and sea. Not understanding each other’s spoken language did not inconvenience our playtime. What lasted in my memory was the fun I had with my friend of one day.

Play is a universal language. Children can discover and invent play anywhere. Play can thrive even amidst hardship. Play can activate the imagination to transform pain into joy.

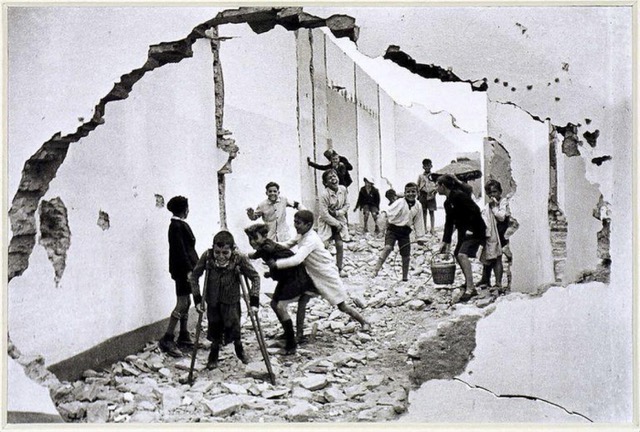

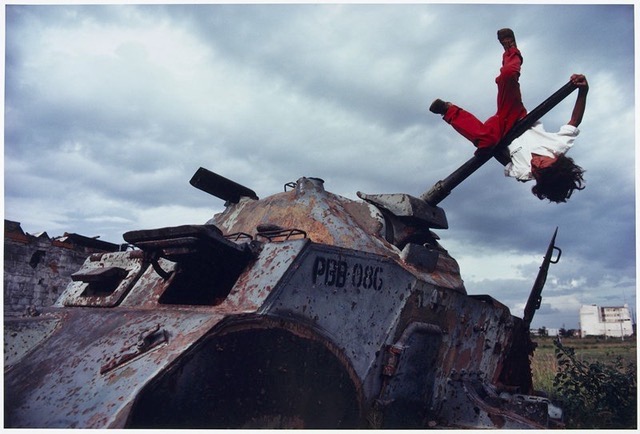

Two photographs document this transformation:

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of a group of children playing in the rubble of destroyed buildings, taken through a hole in the wall. The ruined environment suggests violence, and the nearest child in the foreground is holding himself up on crutches. But most of the children in the photograph are laughing. One boy is laughing so hard that his eyes are closed, and he is holding his belly. Maybe the boy is not injured at all, and the children are merely taking turns playing with the crutches? The children’s boisterous joy contrasts sharply with the destruction around them, and the hole in the wall through which we witness the scene.

James Nachtwey’s photograph captures a child swinging on the turret of a war tank, transforming a tool of destruction into playground equipment. A military tank, fighting in a civil conflict rooted and financed by faraway powers, loses its power through the simple play of a swinging child.

Play can be painful too. And playtime, at some point, ends.

I write this reflection in the days leading up to the presidential election in the United States of America. In less than one week, the future of the world will be shaped by a small percentage of the planet’s population (4.23% according to Worldometer). These are dramatic words, but in the spirit of play, let’s exaggerate. Or is it an exaggeration to say that the economic and military policies of the United States affect people worldwide?

Let’s play the game of 20 Questions. The goal is to ask yes-or-no questions to reveal the right answer:

- Who writes the rules?

- Who benefits most from the rules as they stand?

- Who is allowed to change the rules, and when?

- Who wins?

- Who trusts the election process?

- Who will believe the results?

- Who gets to vote?

- Who gets pushed to the sidelines, and why?

- Who does the pushing?

- Will the rules be followed?

- Who enforces the rules?

- Who doesn’t play by the rules?

- Who is punished when they break the rules?

- Who suffers the consequences?

- If your land is destroyed by weapons made and supplied by the United States, don’t you get a vote?

- Why are billionaires building underground bunkers and compounds?

- When will we stop shattering records of droughts, floods, hurricanes and heat waves?

- Can the natural world survive our inaction?

- Can humanity go on like this?

- Who will not participate in a game they always seem to lose?

I am terrible at this game. I never seem to ask the right questions, so I never find the answer.

Play can reveal power imbalance. One person’s play can be another person’s trauma. Anyone who has ever been a victim of a playground bully understands power imbalance, and the physical threat resulting from facing a bully and their friends. Bullying is a familiar trope in books and films, spanning genres from comedy to horror to feel-good stories. Unfortunately, some bullies never grow out of their tactics, and we too often see them in leadership positions, using the same methods to silence or punish anyone they don’t like or agree with.

Play teaches equity. We learned to protest “it’s not fair” when someone cheated during play or got an advantage that allowed them to more easily win. We learned about winning, losing, and being left out when no one picked us for a team.

Through play, we can transform reality and imagine new worlds. Art does this too. Artists use trial and error, experimentation, curiosity, and a deep understanding of the rules - and knowing when to break them. Artists nurture the work in progress, adapting, questioning, evolving, and playing. Through art, we invite others to join the game, and to invent new ways to play.

Lessons from the playground (adapted from All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten by Robert Fulghum):

- Share knowledge and resources: Let go of deficit mentality. Think creatively. Learn to use the resources available. Learn and educate.

- Clean up your mess: No one should have to clean up after everyone else. When possible, leave things better than you found them.

- Play fair: Acknowledge inequities and work to dismantle systems of oppression. In life, we don’t all start at the same start line. Don’t keep changing the rules to favor the same people.

- Don’t hit people: Not with words, fists, bombs, or bullets.

- Apologize: Say you’re sorry when you hurt someone. Act to stop cycles of harm.

- Play: Ask questions, make mistakes, be silly. Dance, think, draw, and wonder “what if.

- Take turns: No one likes having the same leader all the time. Give someone else a turn. Vote for it.

The game is called How Do We Save the World. Who is ready to play?