Art in the Age of Social Media

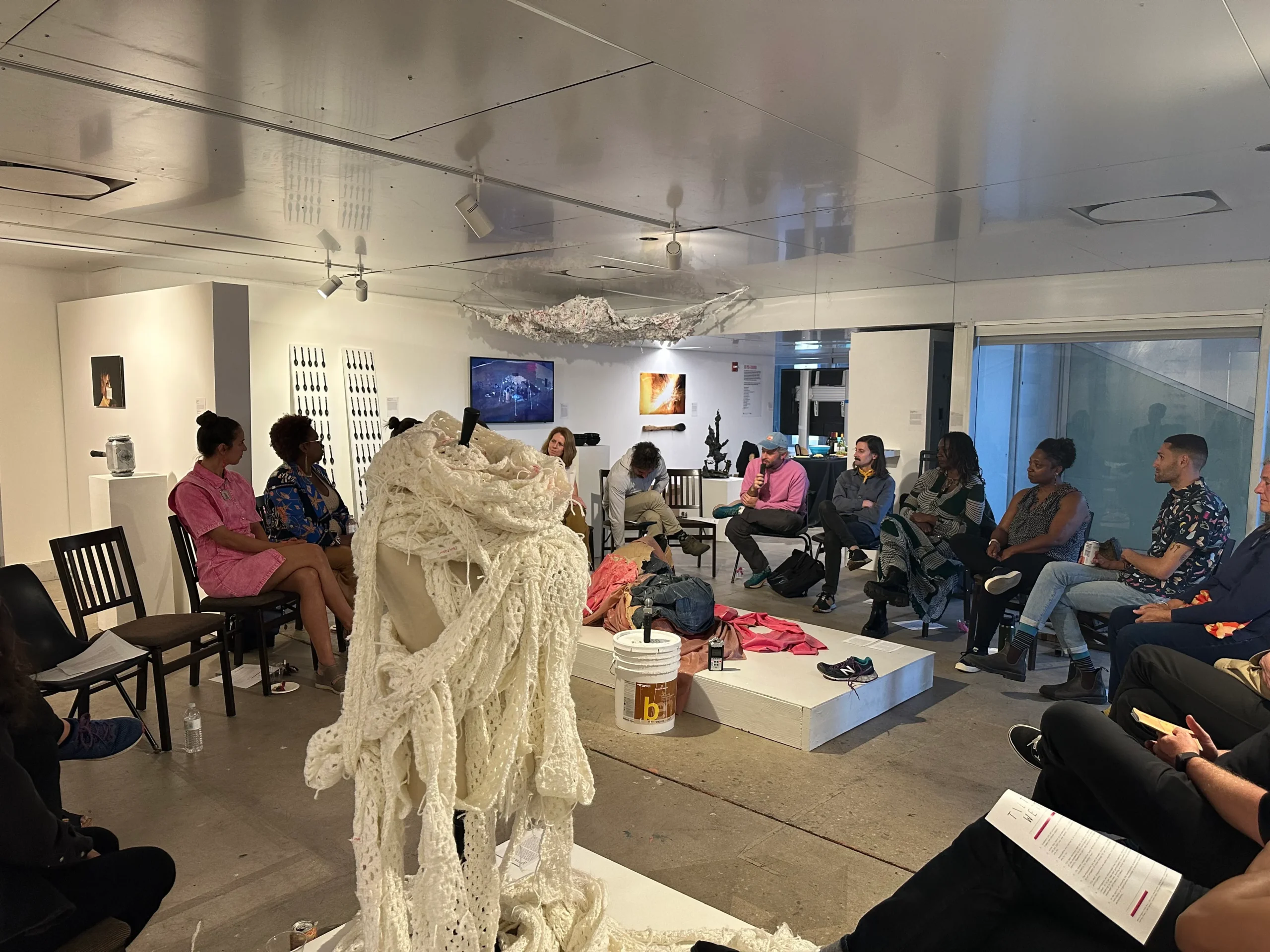

There we were, about two dozen of us sitting in a circle. Something about the arrangement evoked the feeling of a group therapy session for addiction recovery and in the moment when we were called to take our seats, it was hard not to be acutely aware of the stages my own relationship with various social media platforms has been through. I was ready to share, perhaps I wanted to know that I was not alone. Had we all experienced a similar arc? Innocence and curiosity, professional networking and portfolio building, idle addiction, toxic doom scrolling and shit posting. My palms began to moisten. I’ve never been to an addiction support group and I was beginning to feel not only as though I might need one, but that this was going to become one.

Autumn T. Thomas prompted the group discussion with an observation about the cultural shift in the arts from pre to post internet. Having experienced the evolution from analog to digital networks, Autumn noted that the arts had not been shielded from the culture of accelerated production. If before, art was developed through private reflection and encounters with and within the physical world; today, the artist is in a performative role, responding to simulated experiences, managing the (hyper)creation of work under the expectation of opening up processes, sharing — perhaps before work is ready for public consumption/presentation — and perpetuating a culture of consumption of simulated experiences.

It’s 2023 and social media is a pervasive and ubiquitous part of daily life for a majority of internet-connected humans on planet Earth. The utility of the technology is clear. We can all point to experiences where it has helped make connections, opened doors to new communities, or fostered personal or professional growth. On the other hand, a growing body of research reveals the detrimental effects of social media addiction and its unhealthy use, on both mental and physical health. A few have managed to push it out of their lives, but even then, I have to wonder whether deep down the FOMO still smolders.

As an artist, I understood the prompt for this roundtable as inviting a discussion on the role social media plays, could play, or should play in arts practices. How has social media technology impacted the kinds of decisions artists and arts organizations make regarding how they build their careers or organizations, what they share, how much they share, who they share it with? Considerations such as how much of an investment of time and resources to make in post creation, or how to make sure that you’re reaching your audience, must be weighed against what we can reasonably expect to gain from our engagement and how we wish to feel afterwards.

Social Media As A Tool

For artist-users of social media platforms, these sites function as valuable tools for discovering other artists, finding inspiration, learning new techniques, researching culture, connecting to others, forming communities, starting collaborations and growing networks. For the platform creators, the sites are a lucrative system that harvests vast amounts of data on individuals, profiles and categorizes them, and sells their attention to advertisers.

According to an article published by the Pew Research Center, “A substantial share of websites and apps track how people use digital services, and they use that data to deliver services, content or advertising targeted to those with specific interests or traits.”[1] As Richard Serra put it back in 1973, “If something is free, you’re the product.” Though made in reference to television, the remark remains relevant to social media, which reflects a hyper individualization of the ad revenue model used by television, radio and print media. “The feed” is algorithmically populated with content based on the information we provide to the platforms. It has three primary goals: to keep us engaged with the site (scrolling), to gather information about our responses to the content so that the algorithm becomes better attuned to our preferences, and to use that information to build our advertising profile.

The information gathered comprises the totality of our engagement with the platform, its affiliated services, and code hosted by third parties. This includes information we provide when signing up, the content of our posts, our likes, the comments we leave on other posts, who we follow, who follows us, the frequency we post, where we are posting from, how often we open the app, where we are when we open the app, as well as the amount of time we pause on each item in our feeds as we fall into the hypnagogic state of the perpetual (doom) scroll. You don’t even have to be using the app or even signed in. Sites that have a “share” or “like” button for a social media platform and those that use third-party web analytics are part of a wide tracking dragnet. When your browser executes the javascript that powers one of these widgets, it’s phoning home to the social media site to which it’s connected. Every browser you’ve ever used to access your account has its own database entry held by the social media platform and is used to continuously correlate your activity.

A member of our group suggested that social media, as a tool, was akin to a hammer. Another suggested that to complicate the analogy, imagine that this hammer was addictive. Now imagine that the hammer is also watching you, learning your preferences and using what it learns to place things before you that you’re most likely to hit with it. When we use these platforms, we relinquish a degree of our power, control, privacy, anonymity and autonomy. Yet despite the power held by those who designed these systems, they are not totally within their control. Though these platforms are now complex, engineered systems of algorithms aimed at shaping individuals behavior for commercial gains, they will always be more than what they are intended to be. They have their own inherent properties and may behave in ways that run counter to the goals of their creators.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as vaccines were being developed and approved for emergency use, Facebook made a concerted effort to promote them. But anti-vaccine activists flooded the network with “barrier to vaccination” content, using Facebook’s own tools to sow doubt about the severity of the pandemic’s threat and the safety of vaccines. Despite Facebook’s intent to use its own tools for public benefit, Facebook’s algorithms were exploited to do the opposite.[2]

This example highlights the degree to which algorithms and designed systems possess power independent of their creators. This machine autonomy is precisely what social media companies harness and shape; the downside is its potential to be harnessed by other parties.

In theory, it should be possible to use social media as a tool, while simultaneously limiting the degree to which we are used by the platforms. How do we shift the balance of benefits in our favor, and sacrifice as little as possible in the process?

A number of us use social media as a means to an end, an activity to compliment, develop or promote practices based largely outside of or independent of the platforms. To approach this activity with intent and discipline is what I consider to be a practice of using social media. While a valuable approach to limiting the extent to which we are used by the platforms, a deeper form of critique and social commentary is possible by approaching social media as a practice. What this entails is using the platforms with the intent of addressing the role they play in shaping culture and society, and using aesthetics and format of the platforms (UX/UI) as material.

Pioneering artists through history have embraced, experimented with, and incorporated media technologies into their practices. Artists working today to address sub-cultures developing on social media sites, who use the platforms as an integral part of how their work is produced or experienced, and who question prevailing cultural trends driving their development continue this tradition. These practices fall under the umbrella of new media art, more specifically extending net art into the age of social media.

While not a central or necessary feature of new media art or net art, critique features prominently in much of the work that takes its own conditions and circumstances as its subject matter. This self-reflexivity as a critical perspective is a powerful tool to question, push back against, or draw attention to uncomfortable realities that may reside just beyond our field of view. The following three projects are examples from social media’s early years that leverage social media as a practice to engage in self-reflective cultural critique.

The Jogging: Aestheticism and Compulsive Consumption

Liking a post sends a little dopamine hit to its creator, who then seeks the next hit by creating more content and sharing. The more we share and engage, the more we share and engage. We all keep coming back for that hit in a self-reenforcing cycle. Consumption and creation become compulsions when performed on and for platforms engineered around addictive use.

The Jogging is a Tumblr blog created by Brad Troemel and Lauren Christensen. It was started in 2009 as a direct response to the emerging culture of social media and how it was transforming artistic practices. Rather than oppose the hyper productivity and creation/consumption spiral, The Jogging leans into it.

“The name ‘Jogging’ refers to a work flow,” Troemel says. “Constantly moving, and not really focusing on any one thing, but rather to just continue forward.” This always-on approach means practically everything is a potential creative prompt that can be acted on immediately; Troemel has called this athletic aesthetics — the practice of the “aesthlete.”[3]

Excellences and Perfections: Performance and Reality Making

In 2014 artist Amalia Ulman conducted a scripted, months-long performance on her Instagram account, taking aim at toxic cultural practices supercharged by the democratization of image-making and the desire to project success and wealth by reproducing a luxury consumerist fantasy. “As part of this project, titled Excellences & Perfections, Ulman underwent an extreme, semi-fictionalized makeover.”[4]

Using her own personal account, she leveraged the inherent difficulty in separating fact from fiction on social media platforms to such effect that her closer friends oftentimes confused Ulman’s social media performance for her lived reality. This confusion highlights the way fictions promoted on social media platforms produce their own reality, one which has the power to shape our lived reality.

Her critique is subtle but deep. By embracing the cultural logic of social media and taking it to its conclusion, Amalia was able to draw attention to the imbalance in power that persists despite the democratization of image-making and self-publishing, and the degree to which we’ve internalized and reproduced ideals shaped by a wealthy elite to project fame and success — read: the culture of celebrity and perfection.

Escaping the Sandbox

“In computer security, a sandbox is a security mechanism for separating running programs, usually in an effort to mitigate system failures and/or prevent software vulnerabilities from spreading.”[5] A platform’s interface–the graphical elements, font, page layout, and its overall design, both visual and functional–are analogous to the interior design and architecture of a building. The design establishes an atmosphere, or mood, or vibe, if you will, while also signaling how we should navigate a space or platform. User flow and site functionality create permitted and prohibited behaviors. In this way, the UX and UI of social media sites sandboxes users, dictating through the logic of code what can and cannot be posted and how posts will appear.

Glitch art is a subgenre of digital art that encompasses a range of practices concerning errors and artifacts in systems of logic. Early glitch art (pre-2012s) featured artifacts from systems where the data being displayed on screen had become corrupted. What was discovered through chance encounters quickly became the goal of intentional interventions. By exploiting the fragility of digital systems to achieve outcomes unintended by the system architects, glitch artists became akin to computer hackers.

Glitchr’s work on Facebook leverages flaws in the code of the platform to work with the platform’s fundamental design elements and user interface as expressive media, effectively opening doors in the platform’s walls where there were none before. He blurs the line between artist and hacker and in doing so is able to manipulate the frame Facebook places around all content posted to it. By drawing attention to this frame, and oftentimes filling it with incomprehensible unicode gibberish, Glitchr invites us to consider the control that platforms have on shaping our content and the ways in which we express ourselves, and the degree of technological virtuosity required to break free of this sandboxed environment.

“In computer security, a sandbox is a security mechanism for separating running programs, usually in an effort to mitigate system failures and/or prevent software vulnerabilities from spreading.”[6] A platform’s interface–the graphical elements, font, page layout, and its overall design, both visual and functional–are analogous to the interior design and architecture of a building. The design establishes an atmosphere, or mood, or vibe, if you will, while also signaling how we should navigate a space or platform. User flow and site functionality create permitted and prohibited behaviors. In this way, the UX and UI of social media sites sandboxes users, dictating through the logic of code what can and cannot be posted and how posts will appear.

Glitch art is a subgenre of digital art that encompasses a range of practices concerning errors and artifacts in systems of logic. Early glitch art (pre-2012s) featured artifacts from systems where the data being displayed on screen had become corrupted. What was discovered through chance encounters quickly became the goal of intentional interventions. By exploiting the fragility of digital systems to achieve outcomes unintended by the system architects, glitch artists became akin to computer hackers.

Glitchr’s work on Facebook leverages flaws in the code of the platform to work with the platform’s fundamental design elements and user interface as expressive media, effectively opening doors in the platform’s walls where there were none before. He blurs the line between artist and hacker and in doing so is able to manipulate the frame Facebook places around all content posted to it. By drawing attention to this frame, and oftentimes filling it with incomprehensible unicode gibberish, Glitchr invites us to consider the control that platforms have on shaping our content and the ways in which we express ourselves, and the degree of technological virtuosity required to break free of this sandboxed environment.

Shifting Sands Call for Nimble Feet

Today, something has changed, but I can’t quite put my finger on it. All of the projects presented above have gone silent, their last posts made in 2014. Of course, in the time since, there have been several public and controversial changes to the algorithms of platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr as well as changes of ownership and management. Whole new platforms have emerged, like Tik Tok, which isn’t much different in that it makes its money mostly through advertising[6]. Largely, what has remained unchanged is the presence of social media platforms occupying the center of our lived experience on the internet.

So what happened to the creation of critical work about social media on social media? Has the noisy culture of viral celebrity fame drowned out the subtler forms of critique? Have the algorithms, whether by intent or by consequence of their internal logic, simply ignored the potentially ambiguous content? Is it that our culture as a whole has changed, warped by these very social media technologies so that we no longer have the capacity or patience to register works that ask more from us? I refuse to believe that artists have altogether given up and simply gone along unironically with the internal logic of these systems. Perhaps they’re flying below the radar, or are in plain sight. What I know for sure is that the algorithm does not appear to be serving them up to me.

The platforms and their revenue models have been with us for so long at this point that they feel as though they will inevitably persist into the foreseeable future, at least until something new replaces them. However, their algorithms will continue to evolve, augmented and extended by technological advances, mutated and permuted into new forms. As we in the arts wrestle with the role of online technologies in our practices, it will be vital to take up critical positions if we hope to push back or develop alternatives. Perhaps another reason why the critical work eludes me is that it simply isn’t productive to shout about the void into the void, and the more productive route is through direct political action.