Being With What’s So

“Once you start approaching your body with curiosity rather than fear, everything shifts.” –Bessel Van Der Kolk

“When did you become aware of being embodied?”

This was one of the first questions posed by Donna Mejia, who co-prompted Tilt West’s March roundtable discussion, The Body as Medium: Somatics in Creation, with Charlie Miller. The participants’ responses had a consistent theme: the moment of embodiment was often the instant when people became aware of their bodily suffering or their difference from others. Awareness came when what had been invisible or imperceptible suddenly became loud and unmistakable, brought about by immobilizing injury or a long bout of illness. Does this imply that we are almost unaware of our bodies before such a moment? Are we merely sensing beings, incidentally in a body we’ve not had to think about? Ironically, being forced by pain to perceive one’s body as an “other” suggests a contradiction: before this point, while we are blissfully unaware of pain–and by extension, our bodies–in our ‘ignorance’ we are probably the most embodied we can possibly be. In other words, perhaps the less you know (of your body), the more you just *are* (embodied). It is when we become aware of this body, and aware that we inhabit it, that we are faced with answering the question of what exactly that means. If we are aware of being embodied, what then are our bodies telling us that we never before had the impulse to question?

Movement, it turns out, is the original communication, both in human history and human development. It arose before spoken language in prehistoric times [1], and it’s the primary language we have from our time in the womb until around age two. Before we learn words, everything we know about the world is processed as bodily sensation, and much that we express is conveyed through movement. During this small window, our perception of self and our physical experience are one and the same. In his famous declaration on thinking, Descartes unwittingly destroyed the validity of such a fundamentally intuitive way of perceiving the world by positing, “I think, therefore I am.” Five hundred years later, perhaps Descartes’ edict bears re-examining, given that he set humanity on a new path in terms of how we understood ourselves. Where would we be if he had offered instead, “I feel, therefore I am?” And what are the implications of this so-called Cartesian split? In exalting the mind while relegating the world of the body to the primal, we inherently lost connection with our bodies. It follows inevitably then that in this separation from the physical we have come to view our bodies as mere vessels for labor, capital, and worse. We have become distant relatives to ourselves, knowing our bodies more through the eyes and judgments of others than by our own sensations.

Shaping Our Bodies to Fit

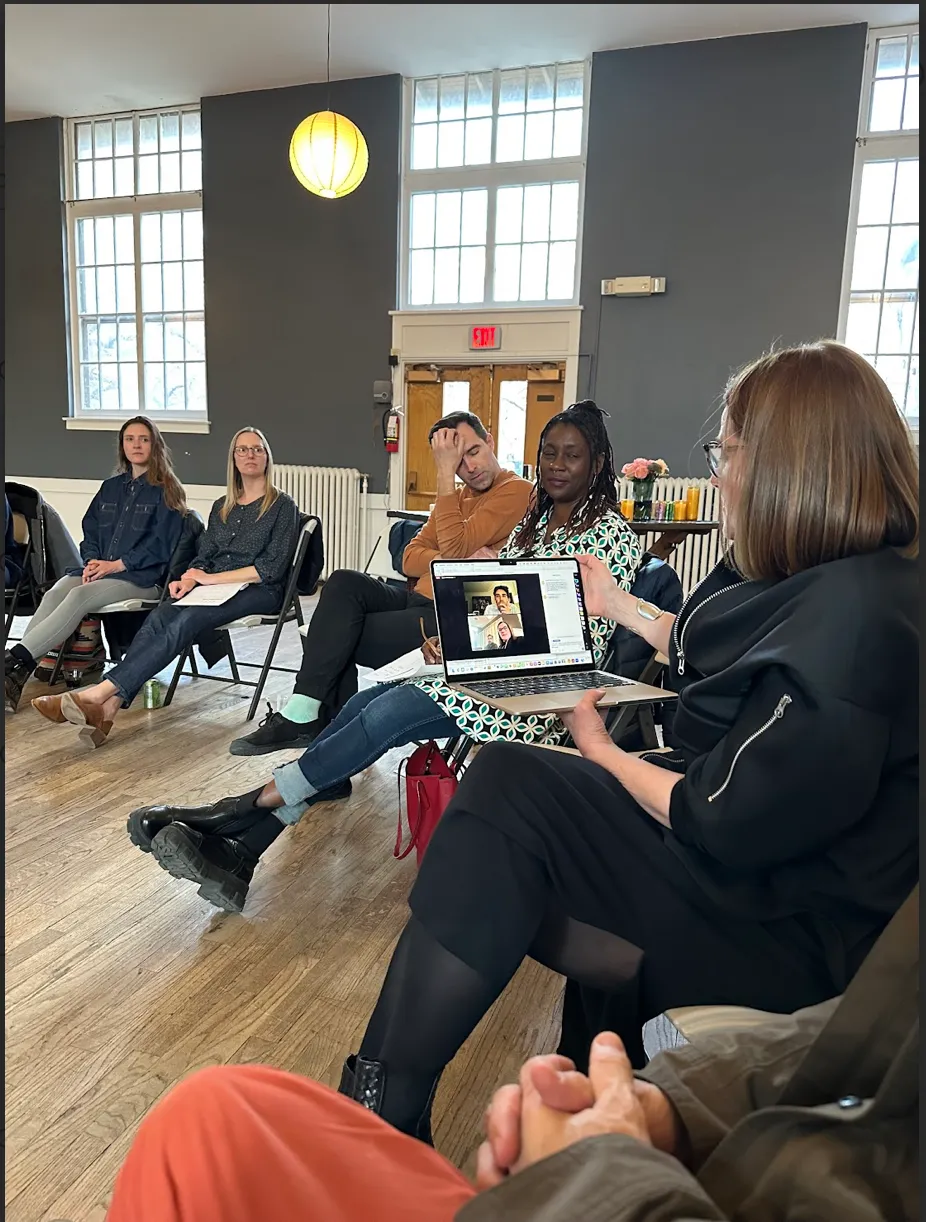

As roundtable participants discussed their experiences of their bodies, there seemed to be far more than the 30 identities in the room; the chimeras of the ideals and disappointments everyone attached to their bodies hovered like an additional cast of characters. People spoke of estrangements, reckonings, negotiations, and reconciliations with their bodies — all distinct moments along the deeply human journey of squaring our identities with our senses of our bodily selves.

When the question was posed, ‘“What does embodiment mean to you?” many seemed hopeful about reconnecting their identities with their bodies. It struck me that this yearning for self-connection is universal; we are all trying to make sense of the multiplicity of co-existing narratives we have developed around our bodies. Within each of us, there are at least three conflicting scripts about our bodies taking place simultaneously: the story we tell ourselves about our bodies; the story about ourselves we tell the outside world by adapting our bodies; and the dream of finding our true selves in acceptance rather than adaptation. As people shared honest revelations of how their bodies were manipulated by outside forces — allowed to be or not; accepted or not — a tangible sense of openness and sincerity emerged. One by one people spoke of what had been silenced within themselves in order to accommodate the demand that their bodies conform, and how the pressure to change their bodies had often come as much from them as the outside world. That this overarching theme of bodies co-opted emerged so clearly was poignant, yet stark.

What have we sacrificed in order to pursue the agenda everyone else has for our bodies? In this schism, there seems to be a deep, shared sense of loss, yet an inability to disengage from a view that the body is a project. We sense this loss, but can only respond with the impulse to fix ourselves: our bodies are projects to heal, judge, make sense of, and remodel, or they are a nemesis of physical pain, imprisonment, and betrayal. The idea of embodiment, though idealized as a blissful unification of one’s familiar identity with one’s physical bodily experience, seems to bring with it a less beautiful truth. Unification of the psychological and physical means that pain hurts every part of us, un-delineated. In fact, many described that it was when they tried to silence their physical pain, and thus control it through sheer cognitive willpower, they felt alienated from themselves. We can no more imagine that suffering ends at the boundaries of our cells than that psychic suffering resides only in our minds; to do so erases the memory and voice of the body. When we only see our body as a physical vessel to transport our true self, it becomes a second-class citizen more easily oppressed by ourselves and others. Likewise, if our disembodied mind is left to process suffering in isolation, we come to believe we are only amalgamations of our thoughts. Embodiment, sometimes painfully, reminds us all: the mind cannot unilaterally think its way into well-being.

In my experience as a dancer and choreographer, the realization that I could be estranged from my body –separated from myself and ‘me’ as I knew her– came suddenly and unexpectedly. This new separation caused just such a collapse of spirit; a separation not only from my body but from an ideal for it I had vigorously maintained but never experienced losing. The environment of the dance world in which I grew up is characterized by demands of perfection, beauty, and virtuosity, and I shaped myself to fit the mold without foresight for how this might hurt me later. Every part of my worth bending to fit this world was a performance — a performance of conformity to directors and other dancers, a performance of flawlessness to the audience, a performance of ceaseless discipline to prove my worth to myself. I have been dancing professionally for nearly 20 years, and have reached expert status in adapting my body as a project to fit standards of perfection I didn’t make but definitely bought into — especially when meeting those standards afforded me my career. Inherent in using your body for art is the daunting truth that its value is determined by the subjective whims, desires, and aesthetic tastes of others. What, then, were my options if my body ceased to fit into this sliver-thin definition of success and artistry, in small ways like turning older than 33 (how dare I?), or in more formidable ways, like fracturing my spine? The only version of myself I knew was a dancer, and ‘dancer’ had one rigid and unforgiving definition rooted in physical perfection — which I suddenly found myself unable to produce. The disembodied fall from my sense of who I knew myself to be, both physical and existential, was much farther than if I had never so adeptly adapted myself in the first place.

Being With What's So: An Act of Personal and Social Justice

What I came to realize (and what so many in the room at Tilt West’s roundtable described) was that in order to come home to my body and find my core body identity rather than conform to an imposed one, I could no longer negotiate an agenda with my physical self. In the brilliant words of one participant, I had to “be with what’s so” — to be with the pain, the changes, and the matter-of-fact, present state of my body. I had to "inhabit my body from within." [2] As a performer, the urge for theatricality called to me even in this most personal of projects: coming home to my body. I decided to rewrite the directions of performance and use my dramatic skills to take back my body instead of constantly offering it to others. Lying in the MRI machine, rather than succumbing to the dread of the circumstances that brought me there, I performed the most beautiful solo of stillness the world had ever seen, for myself and myself alone. Never had there been such poetic stillness! This playful experiment was a serious attempt to reclaim what first drew me to performance while also honoring its real and deep impact in my life, both painfully and creatively. To take back performance would mean I had subverted the very system that had played a role in hurting my body; the weapon that wounded me could be reclaimed as my tool to find myself with physical presence.

This experience brought me back to the dilemma of peering from one’s intellect at one’s body like an object — when you’re trying to repair connections with your body yet still viewing it as an ‘other’ (albeit one you’ve decided you should be nice to), you stay separated. Perhaps what makes it so hard to accept pain in our bodies is that we’ve lost sight of this simple truth: that our minds are our bodies; they are one and the same. Pain runs through our brains, hearts, and mass equally, and even a practice of ‘mindfulness’ offers only the mind to be with the body. What if we could practice bodyfullness, a term coined by somatic scholar Christine Caldwell [3] as a pushback against the limitations inherent in ‘mindfulness,’ which is rooted by its very name in the mind? In being bodyfull, we might reclaim the body’s role in generating meaning and purpose and understand this as an end unto itself. As Caldwell describes it, conscious sensing, breathing, and moving might be seen as a form of bodily prayer. We might be with what’s so, listening within just to hear, looking just to see, feeling just to feel, being with — just to be with. Co-prompter Donna Mejia described her own way of engaging with this idea of being bodyfull as a sort of companionship she found with herself, based on her revelation that ‘your body can’t lie to you.’ When she listened she could hear its truth — or rather, not just its, but her OWN truth.

Being with what’s so is inherently radical. It takes our bodies’ value and function right out of the hands of profit-seekers, employers, societal ideals, and those who oppress and marginalize bodies, and it says our bodies are for ourselves. It shirks somatophobia (the fear and distrust of the bodily self) because if we can be with what’s so, not change what’s so, not judge what’s so, not escape what’s so. It removes the ubiquitous idea that we are projects. When we believe that only our minds are within our capacity to set free, while our bodies stay painfully ensnared, we oppress and cut ourselves off from our wholeness. We liken our bodies to jails; thus becoming unknowing accomplices to our culture’s figurative and literal incarceration of bodies, whether from suffocating beauty and aesthetic standards or actual bodily imprisonment. Accepting our bodies as ourselves through our felt sense of them, rather than othering them, allows us to challenge social structures and oppressive ideologies that seek to make claim on them. It empowers us to experience the world differently despite such ideologies [4].

Being with what’s so in ourselves, then, is not an intellectual truce with our bodies; it’s describing who we are to ourselves by way of sensing as much as conceptualizing. ‘Coming home to ourselves’ might reveal that our deepest identities are ours and ours alone, out of reach of any force that might construct and impose identities to take away from our own. This was captured poignantly by one participant, who detailed the experiences in her body following a traumatic car accident that led to a brain injury. After the accident she would enjoy periods of dissociation whereby she felt she left her body and had visions, a gift of escape from her physical suffering. Suddenly one day this rare side effect disappeared, and she was left to stay in the physical dimension filled with significant pain in a body whose movements she could not control. She had no other option than to ‘be with what’s so’ (in fact those were her words to describe it), yet it was here that she found her most profound spiritual growth and grace. Here she touched her deepest identity, in its fullest, and carried on not despite but WITH everything that was.

When I practice creative bodyfullness, I wonder if I’m looking in on my new form of performance with my own eyes, or if I’m being tricked and am still seeing myself through the gaze of outside judgment (the Great and Powerful Oz that is the ‘dance director’ looking through me). But there are signs that it’s me performing for myself and no one else. There are things that come out of me so intuitively they can only be the signature of my unedited core identity, my body imagination, my me-ness — my mind, body, and soul as just one expression through the medium of my body. When I listen without judgment, conclusions, or even friendship as an impulse, and just allow myself to be with what’s so, I know I’m there with myself. The signature is everywhere: from the innate voice that always comes out in my choreography, to the spontaneous melodies I hum while doing dishes, to the idiosyncrasies of my bodily form, which somehow carry the same essence of ‘me-ness’ made corporeal. I couldn’t invent this signature if I tried (in fact *trying* to be authentic has failed spectacularly, especially when making art). The real art of coming home to the medium of the body is in listening with the heart and not the head. While our brains may process our pain, our hearts emit the strongest electromagnetic field in our bodies, 5,000 times stronger than the brain [5]. Perhaps we might tap into this current not just as a pulse but as a powerful source of knowing ourselves beyond the concepts created by our brains. Maybe Buddhists have the antidote to Descartes’ division–they consider the heart to be the center of human perception. We can use our compassionate hearts to be with ourselves — we have the wattage to do it.