The Right to Be Wrong

Do people have the right to be wrong? This question anchors arguments about censorship, mooring interlocutors in stormy waters.

When the censor answers, “No,” that response comes from the conviction that ████████ is too harmful to be heard. At its best, censorship can be a loving gesture, a protective hand pressing against vulnerable ears. At its worst, censorship is a selfish maneuver, a shield around the censor that deflects criticism.

When the heretic answers, “Yes,” that rejoinder comes from the conviction that nothing is too harmful to be heard. At its best, heresy can be a rejection of patronizing attempts to shelter, an insistence that treating people as fragile is both an insult and a self-fulfilling prophecy. At its worst, heresy is a shallow excuse for bad behavior, a justification for malice.

Of course, heretics don’t believe that they’re wrong, and sometimes they’re right about that. “The truth hurts,” they might say. Other times, they really are wrong. But the right to be wrong does not hinge upon an objective analysis of the truth. In those stormy waters, there’s too much salt stinging peoples’ eyes to find the truth; the compass was washed overboard; dark, gray clouds cover the stars.

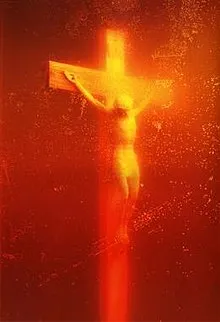

When people evaluate the right to be wrong, what they care about is how much pain the heresy causes, not how true the heresy is. And so, in navigating between the censors’ “no” and the heretics’ “yes,” we must ask a follow-up question: What results in more harm — the risk of being wrong or the elimination of that possibility? It is instructive to consider real-world examples when mulling over complicated questions like this, because the devil is always in the details. Exhibit A is Andres Serrano’s 1987 photograph, “Immersion (Piss Christ).”

Serrano submerged a wood and plastic crucifix in a vat full of his own urine and then photographed Christ on the cross through the bubbling, amber fluid. Of his motivations, Serrano said, “I’m a Christian artist making a religious work of art based on my relationship with Christ and The Church. The crucifix is a symbol that has lost its true meaning; the horror of what occurred. It represents the crucifixion of a man who was tortured, humiliated and left to die on a cross for several hours. In that time, Christ not only bled to death, he probably saw all his bodily functions and fluids come out of him. So if ‘Piss Christ’ upsets people, maybe this is so because it is bringing the symbol closer to its original meaning. There was a time prior to the 17th century when the only important art, the only art that mattered, was religious art. After that, there were very few contemporary art pieces that were considered both art and religious, and ‘Piss Christ’ is one of them.”

Serrano’s detractors attributed other motives to him, and they accused him of blasphemy that hurt believers. A 16-year-old boy bludgeoned “Piss Christ” with a hammer at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne because his mother wept after the Gallery decided to display it. That Australian retrospective of Serrano’s work was promptly closed, so that violence would not spread to the simultaneous Rembrandt exhibition. A few years later, in Avignon, France, another Serrano retrospective closed after “Piss Christ” was hammered again. Eight hundred protesters besieged the Lambert Gallery, and museum staff received death threats. (Serrano has also received death threats.) Perhaps most infamously, U.S. Senator Alfonse D’Amato (R-NY) tore up a copy of the photograph while arguing for the need to review how the National Endowment of the Arts selects artists to support with tax dollars.

Senator D’Amato alleged, “In naming it, [Serrano] was taunting the American people. He was seeking to create indignation. That is all right for him to be a jerk, but let him be a jerk on his own time and with his own resources. Do not dishonor our Lord. I resent it, and I think the vast majority of the American people do. And I also resent the National Endowment for the Arts spending the taxpayers’ money to honor this guy.” But the artist insisted, “I am not a heretic. I like to believe that rather than destroy icons, I make new ones.” Serrano also clarified that, “To set the record straight, I received not a whole grant from the NEA, but a partial grant. I received $15,000 from an organization that had received $5,000 from the NEA. At the time that I received that money, I was a poor artist. I made no income, I paid very little taxes. Since then, because of the fact that my name became so prominent and I sold so much work, I’ve paid millions of dollars back in taxes. You know, so you have to figure, it was a great investment for the government and for the United States.”

And not every Christian opposed Serrano’s “Piss Christ.” Standing in contrast to Dr. George Pell, the bishop who tried to invoke dusty blasphemy laws last used in 1871 to censor the photograph, is Sister Wendy Beckett, the British nun and art critic who became a beloved interpreter of culture in the 1990s. When asked if “Piss Christ” offended her, Sister Wendy explained, “Well actually no, because I thought he was saying, in a rather simplistic, magaziney-type of way, that this is what we are doing to Christ. We’re not treating him with reverence. His great sacrifice is not used. We live very vulgar lives. We put Christ in a bottle of urine — in practice! It was a very admonitory work. Not a great work, one wouldn’t want to go on looking at it, once one had seen it once. But I think to call it blasphemous is rather begging the question. It could be, it could not be. It’s what you make of it, and I could make something that made me feel a deep desire to reverence the death of Christ more by this suggestion that this is what, in practice, the world is doing.”

Her interviewer pressed her on this point, asking if there are objective standards for great art, and Sister Wendy went on to say, “If, continually, people look and look and always come away enriched, then it’s a great work. But it takes time, you see, to discover this, so it’s not just flavor of the month or flavor of the year. That’s why it’s very hard to make judgments on works of art — we have to wait.” In other words, if judging art requires innumerable viewings for decades or centuries, then blocking the view hides the truth. But remember, denying the right to be wrong is more about preventing pain than accessing truth.

The “Piss Christ” censors believed that Serrano’s photograph hurt both believers and God because Serrano literally pissed on their religion. And yet, their censorship became a media sensation. “Piss Christ” was reprinted in news articles, and Serrano was interviewed for a documentary about him and his work. His photographs began to sell for so much money that he has paid millions in taxes to the U.S. government. How many more people saw “Piss Christ” because some tried to censor it?

To return to our follow-up question, did this example of censorship reduce harm? By the censors’ own standards, more Christians were harmed because of the proliferation of “Piss Christ.” Nobody could un-see the image.

A similar event unfolded thirty years later.

Exhibit B is Dana Schutz’s 2016 painting “Open Casket.” Schutz based her painting on a photograph of Emmett Till’s body, lying in an open casket after he was mutilated and shot by racist white men during the Jim Crow era in Mississippi in 1955. Of her motivations, Schutz said, “I made this painting in August of 2016 after a summer that felt like a state of emergency — there were constant mass shootings, racist rallies filled with hate speech, and an escalating number of camera-phone videos of innocent black men being shot by police. The photograph of Emmett Till felt analogous to the time: what was hidden was now revealed. The painting is very different from the photograph. I could never render the photograph ethically or emotionally. I always had issues with making this painting, everything about it. And it is still uncertain for me.”

Schutz’s detractors attributed other motives to her, and they accused her of exploitation that hurt black Americans. “Open Casket” debuted at CFA Gallery in Berlin in 2016 without incident, in a solo show titled Waiting For The Barbarians, which included paintings that the gallery press release described as “terrifying events where time seems stopped.” But when Schutz displayed it again in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, an artist named Parker Bright stood in front of “Open Casket” with other protestors, wearing a t-shirt that read “Black Death Spectacle,” and argued that the piece was an injustice to the black community. Soon after, British-born, Berlin-based artist Hannah Black wrote a letter to the curators, co-signed by over 30 other artists, arguing for the removal — and hopefully also the destruction — of “Open Casket.” The Whitney Biennial curators, Mia Locks and Christopher Lew, declined.

In the letter, Black wrote, “with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum…. In brief: the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time…. Although Schutz’s intention may be to present white shame, this shame is not correctly represented… The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights…. Even if Schutz has not been gifted with any real sensitivity to history, if Black people are telling her that the painting has caused unnecessary hurt, she and you must accept the truth of this. The painting must go.” But Schutz insisted that the painting had never been for sale, and, “I don’t know what it is like to be black in America but I do know what it is like to be a mother…. In her sorrow and rage [Mamie Till] wanted her son’s death not just to be her pain but America’s pain. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension. Their pain is your pain. My engagement with this image was through empathy with his mother…. I don’t believe that people can ever really know what it is like to be someone else (I will never know the fear that black parents may have), but neither are we all completely unknowable.”

And not every black artist opposed Schutz’s “Open Casket.” Standing in contrast to Dr. Lisa Whittington, who also painted Emmett Till and thinks that Schutz should have painted the white actors in his story instead, is Coco Fusco, whose mother never allowed her to visit the Deep South. (Fusco’s mother escaped the Cuban revolution and immigrated to New York just before Till’s murder, so that his death was her introduction to the U.S.) In an essay she penned for Hyperallergic, Fusco explained, “I find it alarming and entirely wrongheaded to call for the censorship and destruction of an artwork, no matter what its content is or who made it. As artists and as human beings, we may encounter works we do not like and find offensive. We may understand artworks to be indicators of racial, gender, and class privilege — I do, often. But presuming that calls for censorship and destruction constitute a legitimate response to perceived injustice leads us down a very dark path. Hannah Black and company are placing themselves on the wrong side of history, together with Phalangists who burned books, authoritarian regimes that censor culture and imprison artists, and religious fundamentalists who ban artworks in the name of their god.”

Fusco went on to write, “The authority to speak for or about black culture is not guaranteed by skin color or lineage, and it can be undermined by untruths…. [Hannah Black] claims that Mamie Till wanted her son’s body to be visible to black people as an inspiration and a warning; however, according to Emmett Till’s cousin Simeon Wright, who was with him the night of his capture and attended his funeral, Mamie Till said ‘she wanted the world to see what those men had done to her son’ (my emphasis). There was no exclusion of non-black people implied, nor was it a deviation from the custom of having an open casket. That casket was donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture by Till’s family to be on view for all, not just black, people…. Those photographs galvanized the Civil Rights Movement: activist leaders strategically and adeptly circulated them to encourage blacks and whites in the North to join the struggle, and in order to shame politicians by casting doubts on America’s adherence to its democratic ideals.”

The “Open Casket” censors believed that Schutz’s painting hurt black Americans because Schutz behaved with presumptuous entitlement. And yet, their attempts at censorship became a media sensation. “Open Casket” was reprinted in news articles, and Schutz is still showing her paintings despite attempts to de-platform her. It is too soon to tell how her career will be impacted in the long-term, but we can still wonder: How many more people saw “Open Casket” because some tried to censor it?

To return to our follow-up question, did this example of censorship reduce harm? By the censors’ own standards, more black people were harmed because of the proliferation of “Open Casket”. Nobody could un-see the image.

In both the Serrano and Schutz scenarios, an artist appropriated an image of a mutilated, murdered man that is sacred to a particular population. The lynching of Emmett Till became a sacrifice for black Americans; like Christ, his parent tried to help heal the world through his suffering. Of course, there are also obvious discrepancies, namely that Mamie Till did not choose to sacrifice her only son. Herein lies another layer of harm in these particular arguments over the right to be wrong: what kind of reverence do we owe to the dearly departed? Perhaps the censors in both scenarios sensed that these artists were breaking the millennia-old taboo of “speaking ill of the dead” when they gave themselves permission to use these sacred images.

While Serrano’s provocative title seemed like an undeniable insult to his Christian critics, Schutz did not obviously speak ill of the dead. Instead, her critics protested against her speaking about the dead, about their dead. Censorship is inherently tribal, so that when it is a loving gesture, its protective hand only extends toward members of the in-group; at the same time, the other hand strikes the heretic. In the recent history of tribal conflict, if Serrano was a major figure in the culture wars of the ’90s, then Schutz may be remembered similarly within this decade’ debate over identity politics.

The similarities between these scenarios are striking, as are their differences. Serrano’s critics largely came from outside of the art world, while Schutz’s largely came from within. As a result, Schutz’s career is threatened by the disapproval of her peers in a way that Serrano’s never was, and it is unlikely that Schutz will make millions more dollars because of her controversy. There was also collateral damage, because black artists who painted about black pain in the 2017 Whitney Biennial were overlooked in favor of scrutinizing and punishing Schutz. How many people remember the names of those artists?

A crucial difference between the “Piss Christ” and “Open Casket” controversies is that in Schutz’s case, no death threats were issued, no exhibitions were cancelled, and no artworks were destroyed. This is to the credit of Schutz’s detractors and to the shame of Serrano’s. There are only two ways to resolve conflict — words or blows — and only one of those can literally end in murder. It’s not exactly true that, “sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me,” because people hurl plenty of heartbreaking words, even at those they love most; but it is true that stoning is a form of execution, so that playground retort is on to something. If the only alternative to words is blows, is it wise to curtail the use of words?

Censorship may seem ineffective in these examples, although the practice has sharper teeth in societies that do not protect freedom of speech and expression. However, even in the U.S. where free speech is protected more than anywhere else in the world, attempts at censorship can have lasting consequences. Heretics are always punished in public to remind other people to hold their tongues, and it is impossible to measure how much has been left unsaid. The media sensation does not merely propagate the offensive image. It also propagates a threat: You better not say or paint the wrong thing.

The best way to avoid saying or painting the wrong thing is to just not think about it. If it’s not in your head, then it can’t slip out of your mouth. Put another way, censorship says “no” to the right to think… whether that’s thinking critically about the shortcomings of one’s own religion; thinking mournfully about the racism of one’s own country; or thinking about any number of other things. Censors help people not think by passing out scripts that tell them what to say. How much harm can come from forbidding the right to think?

One such harm is bad art. Creativity is unscripted. Without the right to think and be wrong, artists cannot try anything new. Discoveries tend to be more or less stumbled upon, after a great many mistakes. But in lieu of exploring the human condition, censorship replaces art with propaganda.

What is the value of art, without the right to be wrong?