What Censorship and Permission Mean for Voices Scripted by a Dominant Culture

Let’s be honest, censorship can be discussed, argued, and evaluated ad nauseum. Like any social or political issue, everyone has an opinion, and the opinions are varied. We value the notion of neutrality in such discussions, the idea that a free or open exchange of ideas yields “truth.” But what happens when voices are not given equal weight, when the historical and cultural context that informs some voices is suppressed before the conversation even begins?

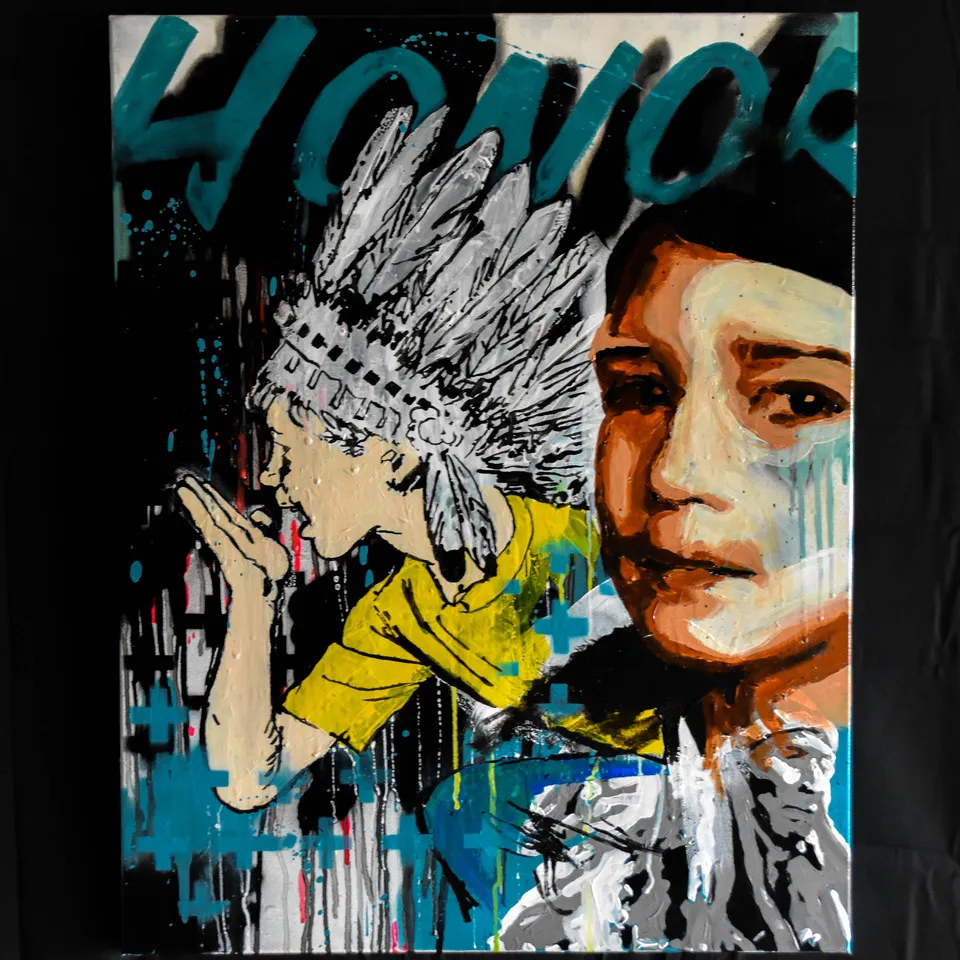

I am a person of color, as they say. More specifically, I am an Indigenous person, as well as being an artist. I live in a society in which the image, likeness, and existence of Indigenous people is scripted by popular culture — a culture that is not ours. In my career, censorship has been weaponized to maintain these popular tropes and to escape the discomfort of a truth that is different from that of the popular (mis)understanding.

For those of us who are “other,” there is aggression, even evisceration, in censorship. The term “other” refers to the social status of people who are inherently different than those of the dominant culture. “Othering” emerged out of European Colonialism, where defining who is “good” or “normal” was an important part of conquering the world. “Othering,” by extension, became part of the history and vernacular of the United States, where the role played by people of color was either forced labor or straight-up genocide.

Embedded in this history of “othering” is the authority to define and inform who Indigenous people are across generations. What is latent in this definition is the positioning of the worth of one people, culture, and story over that of another. To define a people as savage is to make them less than — less smart, less desirable in appearance, less worthy than anything in Western culture — even to the people themselves.

So, how does this relate to permission and censorship in art? Growing up in the United States taught me that, for someone like me, submission is rewarded over seeking permission. Censorship becomes a means of quieting the voices of those who seek permission to define their own sense of existence and identity.

Some context is necessary. Just about everything indigenous, from sports mascots to films to literature to art — yes, even art — is defined by a limited set of images: the man in the headdress, or the submissive maiden. Being defined by headdresses and buckskin maidens is to be beholden to an image of Plains Indians, who represent a fraction of the indigenous tribes and traditions. There are 577 federally-recognized tribes in the U.S., and several hundred more that are not. There are over 300 different languages and multiple dialects within each language, and at least as many different traditions, origin stories, and cultures. And yet our “Indian-ness” is judged in relation to the dress and even the facial features of about a dozen tribes. Whether one is Navajo or — like me — Paiute, we must present as a Plains Indian to give you, the non-Indian, context.

This carefully-scripted context quite literally will inform what is permitted in art by Indigenous people. There is a silent, insidious censorship at work, in which curators and collectors decide whether an Indigenous artist’s work looks Indian enough to be authentic. Anything outside the canon of Western understanding of Indigenous identity is cast aside as too complicated, too uncomfortable, even offensive. Often, we don’t even get to the point of entering the conversation.

In 2016, I was invited to participate in an exhibition of more than 40 artists representing diverse nations, religions, races, sexual orientations and genders at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. — a career milestone for any artist.

Just as things were ramping up, the Office of Public Affairs at the Smithsonian approached the head curator of the exhibition with concerns; the Office wanted to perform an extra layer of vetting of each artist. The curator was tasked with presenting the artists and their proposed work to a committee, which happened to be entirely Caucasian. Two artists were singled out for extra scrutiny, and I was one of those artists.

In my performance work, I deliberately engage tropes and cultural stereotypes in order to disarm them. When the curator showed the committee a photograph from my performance entitled, “The Last American Indian On Earth,” which shows me clad in a faux Indigenous outfit and a fake (albeit decently made) headdress, the response was an audible gasp. The idea of my proposed performance was to embody the Indigenous stereotype and document public reactions to it. I certainly got a reaction.

The committee presented me with a list of requirements that went something like this:

1. You can NOT talk about the Washington Redskins. You cannot use the Redskin logo or insignia, and you are not allowed to use the word “Redskin” at any point of the weekend and performance.

2. Your work needs to be submitted to and checked by the director of the National Museum of American Indians.

3. Validation of your right to create such works needs to be presented to the National Museum of American Indians director. This can be in the form of proof of tribal enrollment, certificate of Indian blood, or other documentation proving your lineal right to be listed as an Indigenous artist.

4. Failure to adhere to these items will remove you from the exhibition and be considered a breach in contract.

I was blind-sided. Never in my years as an artist had I been required to “prove” either my own Indigeneity — by tribal registration or blood quotient — or the “Indian-ness” of my ideas. Can you imagine them requiring participating black artists to check their work with the newly-erected National Museum of African American History and Culture, or Asian artists to go to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (also on the National Mall under the Smithsonian umbrella), or — heaven forbid — the few White artists in this show to go to… I don’t know… the National Museum of American History? The football team mandate was gratuitous, as I never proposed anything having to do with the mascot. “Redskin” is a dictionary-defined racial slur. And yet, standing on the National Mall in one of the pre-eminent art museums in the nation, I was pre-emptively told not mention it, so that I would not offend the non-Indigenous football franchise.

Because I wanted to exhibit at the Smithsonian, I went through their vetting process with regard to each aspect of my work, but I kept a few tricks up my sleeve. I changed the name of my piece to “The Indian Voice Removal Act of 1879–2016.” 1879 was the year the first government-owned Indian boarding school had opened, something I consider to be an early official government action to eradicate the cultural voices of Indigenous people. For this show, I had proposed to erect a giant tipi as a backdrop to a performance piece. I told the committee that the tipi would be filled with images of Indigenous people. What I didn’t tell them is that I would deface each painting, which were all black and white, with a big red “X” over the subjects’ mouths. And for my performance piece, I would place a large, white handprint over my own mouth. When people directed questions to me, a white man dressed as an anthropologist with a name tag that read “Cornelius Smith, Cultural Interpreter” would respond instead.

My artwork became a protest — a response to censorship and an echo of the silencing of Indigenous voices by Western powers for centuries. Censorship remains a core aspect of my work. I have been required to jump through hoops that other artists — even other artists of color — would never be asked to tolerate because of the profound discomfort that arises when I challenge the narrative imposed on my “otherness.” The Smithsonian was concerned by my use of appropriation (appropriation is bad, right?) without ever considering that the images I embodied had themselves been appropriated by the dominant culture.

In a conversation about censorship and permission, all voices are not equally situated because of the weight of history. For indigenous artists like me, that history is so endemic as to be rendered invisible, even as compared with that of other people of color. Times are changing, but censorship remains in play as an arsenal to maintain dominant narratives even in the most celebrated art institutions.